This article by Colin Zacharias originally ran on Powder Cloud on January 20, 2021 and has been reprinted with their permission.

You can read the original article here, and check out the rest of the site while you’re at it.

Terrain Tip #4: Know Where Not to Go

Knowing where not to go is the most important backcountry decision you’ll ever make.

When it comes to managing avalanche risk in the backcountry, that overused dictum “know before you go” could be rephrased as, “before you go, know where you don’t want to go.” In this feature, we dig deeper into the statement made in the “Terrain Tips Intro” that behind every good backcountry decision is a terrain choice that reduces the risk.

In the ’80s I entered the heliski guiding world from a resort avalanche-control background. Back then, a ski guide in the wilds of the B.C. backcountry would never have the same decision-making confidence that came with a ski area’s historical record-keeping, run compaction, fenced-off closures, and an unlimited supply of explosives. When faced with the prospect of finding safe terrain within a 1,500-square-kilometer wilderness tenure, the decisions of where you go, when you go, and how you go can become uncertain—and are bracketed by the dire consequence of being wrong. You realize that if you are going to do this at all, you gotta do it right.

It impressed me that the heliski company’s experienced teams had a strategy that reduced the risk day after day, winter after winter. I could immediately see that the two most important decisions on any given day were made in the morning guide meeting, not in the field. Simply put these included 1) adopting a terrain mindset that reflects both an analysis of the risk factors and a willingness to limit exposure, and 2) agreeing on slopes to avoid.

Trip Plan

“Those who ride together decide together.

Listen to every voice. Challenge assumptions. Respect any veto.”

(developed for AIARE)

Adopt a Terrain Mindset

During our morning ski-guide meetings, time was set aside to discuss and document our runs as open (green) and closed (red). This process of choosing or avoiding ski runs was based on criteria including avalanche hazard, forecast visibility and flight risk, non avalanche–related mountain hazards, guest skills, and snow quality. After reviewing weather, snowpack, and avalanche hazard factors, it was apparent that most guides would already have a morning mindset that would frame the team run-list discussion and operational plan.

This mindset was a mental attitude or disposition that would evolve from each guide’s hazard assessment, local knowledge, and personal level of risk acceptance. The mindset defined an unspoken, internal dialogue that illustrated each guide’s perception of conditions, terrain, and level of uncertainty and confidence: “Today, I’m a bit uncomfortable. I’m choosing a drainage with straightforward options, keeping it mellow, and staying out of harm’s way.”

Importantly, the mindset informed our team’s decision to open or close ski runs and helped to subdue habit and desire—two semi-automatic processes that could bias our daily terrain choices. Each guide had a personal and at times cryptic way of expressing their mindset. Phrases such as “now is not the time to roll the dice” might reflect uncertainty, or “drop off low and pick up high” may indicate one’s strategy to manage poor visibility and high freezing levels, or “stay on-line only” could mean only ski the most conservative, risk-free runs in each drainage, or “take a look, but take it easy” could urge a plan to get the guests out for a few safe runs, make some important observations, and come home early.

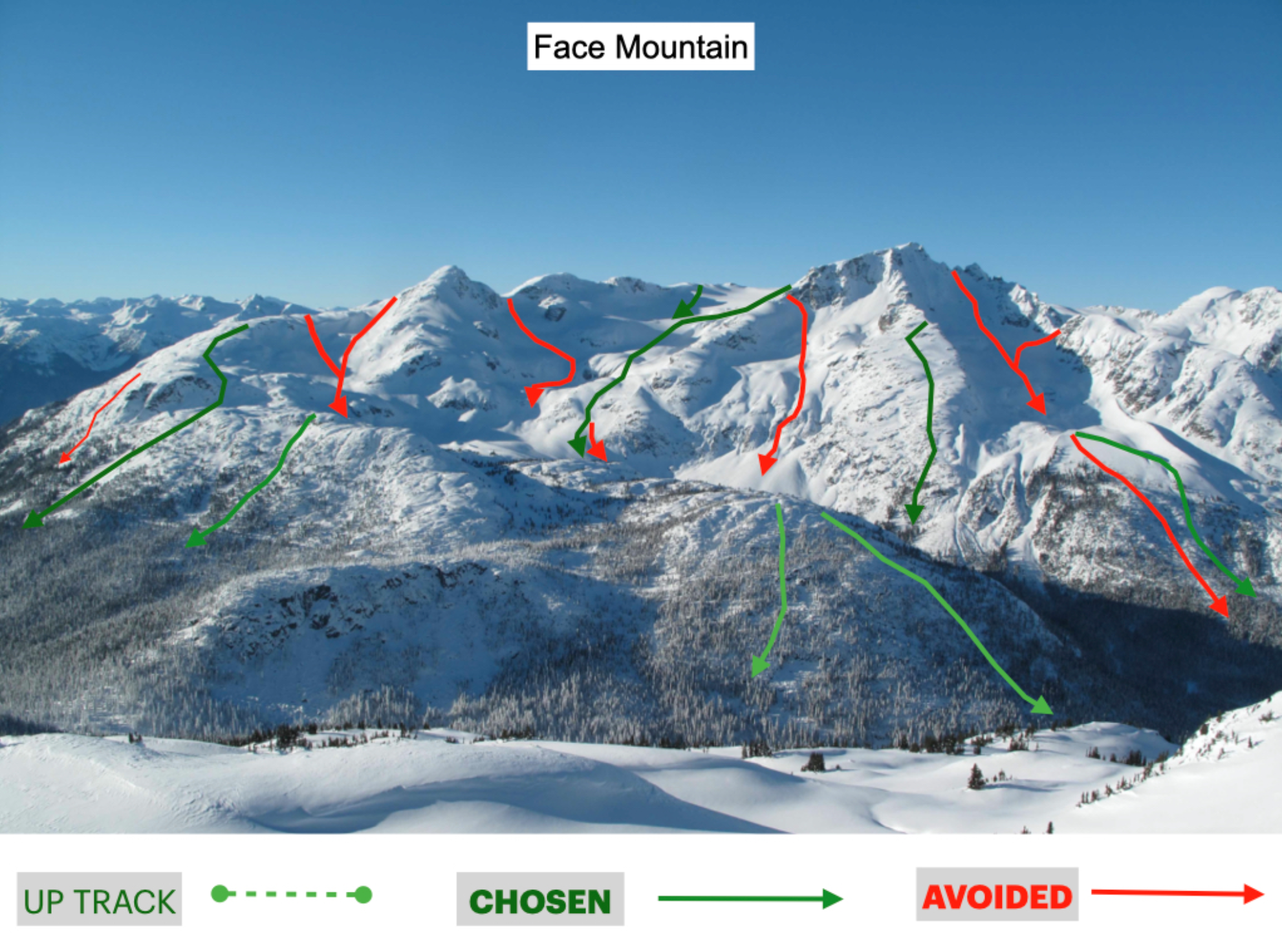

The Canadian Mountain Holidays (CMH) ski guide and perennial thinker Roger Atkins, formalized his impressions into a “strategic mindset” that was incorporated into the CMH operational plan during the 2000s and presented as an International Snow Science Workshop (ISSW) paper titled “Yin, Yang, and You” in 2014. During his presentation, Atkins defined CMH’s seven operational mindsets, from Assessment (scouting mission) to Open Season (most runs are safe). The legendary ISSW session was an epiphany for many attending operators, and Atkins’s strategic mindset is now a decision-making aid employed in the guiding and avalanche industry. Even the backcountry avalanche bulletins are starting to include the forecasters’ mindset and disposition in “the bottom line” or headline. Banff National Park prefaced their December 30, 2020, report with the inclusion, “conditions are excellent…. Now is a good time to be in the mountains.” The following mindset choices are an adaptation of the Atkins and CMH principles, tweaked to be useful to the backcountry recreationist’s daily trip plan (developed by the author, Howie Schwartz, Bruce Jamieson, and Brian Lazar).

Choose one mindset for the day

Click the image below to explore each mindset in the original article on Powder Cloud.

Select Your Route and Agree on Slopes to Avoid

At this point in your morning trip plan, you have analyzed today’s risk factors, read through the mindset descriptors, and begun to formulate a strategy. You adopt one mindset for the day, knowing that this will frame your perspective and support any subsequent field decisions. You are ready to select terrain and to mitigate the risk.Using mapping and satellite imagery applications, photos, and guidebooks, you select a drainage that will provide travel routes suited to today’s team, conditions, and hazards. You discuss where you may be exposed to today’s avalanche problems and agree upon the appropriate up-track routes and descents. You also select and agree upon an alternate route in case conditions turn out to be different than expected.

Most importantly, you point out and agree on the key slopes the team plans to avoid. You can mark your routes on digital maps and/or photos and save them to your smart phone to provide a valuable field reference.

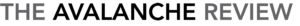

The following examples are annotated to indicate terrain that has been discussed. The green lines are selected routes, and the red lines are the routes to avoid.

Closing remarks

During the trip plan, when your team adopts a mindset and consensually agrees to avoid terrain, you do not break that promise. Once in the field, if conditions are better than you expected you can always agree to ski the line the next day—given the same conditions. Even if you were wrong in a good way, this “24-hour rule” applies a margin for error that allows you to make an informed decision tomorrow rather than one based on speculation and desire today.

The terrain mindset contextualizes terrain choices and supports subsequent field decisions. At the day-end debrief we can review the decisions made relative to the mindset we adopted. Importantly this informs how we utilize the mindset on subsequent days. Adopting a mindset prior to selecting a drainage, routes and slopes has become an essential decision-making support tool.

The idea of closing terrain prior to departing the office was also game-changer for me. Back in 1989 I was the kind of guy that thought “the forecast is fiction” and “I’ll wait till I get out there and see for myself.” This all changed when I experienced the benefit of discussing and anticipating terrain at home in a low-stress environment. Discussing each run and feature brings up past avalanche events, other’s terrain use strategies, and forces the mental gymnastics of visualizing exactly where mountain hazards existed on specific slopes. This visualization exercise has given me the navigation skills and snowpack and terrain memory that I value today.

Colin Zacharias is a consultant and educator in the avalanche and mountain guiding industries, and an IFMGA/ACMG mountain guide. He resides on Vancouver Island.