Story & photographs by Todd Richards, originally published in TAR 41.2. Trigger warning: this story contains an explicit description of a near-death encounter via avalanche.

FEBRUARY 14, 1989, TELLURIDE COLORADO, 12,227’

We rode a chairlift called The Plunge to the top and then followed the booted footprints of countless other backcountry seekers. 200 yards later we passed through the gate, a legal declaration of independence highly valued in this box canyon town. The hike was short, a small effort to access thousands of acres of untracked terrain made even more delicious by overnight snowfall. It was my day off from teaching rich people and their bratty kids how to ski. Bright sunshine, no wind, and temps barely below freezing meant relatively light clothing. Tinted goggles or sunglasses were mandatory under the brilliant high elevation sunshine.

Moments later my feet surfed effortlessly on wide open untouched powder. Silent three-dimensional parabolic curves propelled only by gravity—as perfect as it gets. I left behind only rhythmic grooved arches, proof of accurate steering, weight distribution, and angulation skills I’d honed to precision. A gracious dance splitting time between catch and release, each one better than the last, by far the best turns I’ve made in my life, dozens and dozens of them.

This, more than my hundredth day in a row, made me more fit and skilled than any previous time in my 23 years and 25 days of life. Adrenaline and joy aside, I would have a heart rate near resting pace. Never had I acquired such a level of talent in anything before. I was bowling only strikes, hitting only home runs, and throwing only touch-downs without even breathing hard. I hoped my two companions would feel the ease of this time/movement but doubted it.

I descended in bliss perhaps 400 vertical feet towards a large rock outcropping I had discovered the previous day with Vaughan, a delight- fully happy New Zealander. Perched on the steep slope under the deep blue sky, I planted my glove-sheathed poles uphill to retrieve my camera in hopes of capturing him as he approached from above. Alas, I again forgot to remove the lens cap in time to record his movement and glowing face of joy. He was now standing in front of me, speechless from his own experience. No matter— there would be many more chances to chronicle this wonderful day with the stunning Bear Creek Canyon as a backdrop. Paul was still above us. I raised my camera and pointed it upward to place him in the viewfinder.

Then I felt it.

A low rumble detected in my feet with custom footbeds, tight buckles, and perfectly formed liners. I’d learned to ‘tune into your feet’ this season; where every skiing action is both started and controlled. The entire hill vibrated. It purred like an enormous lion. I’d never felt, heard, or seen an avalanche before, but knew immediately the instantaneous change from a glorious to perilous day.

I glanced upward to see the monster, hundreds of feet wide and several stories tall. It was as defined as a thunderhead cloud containing immeasurable amounts of mass but already moving at a tremendous speed directly at us.

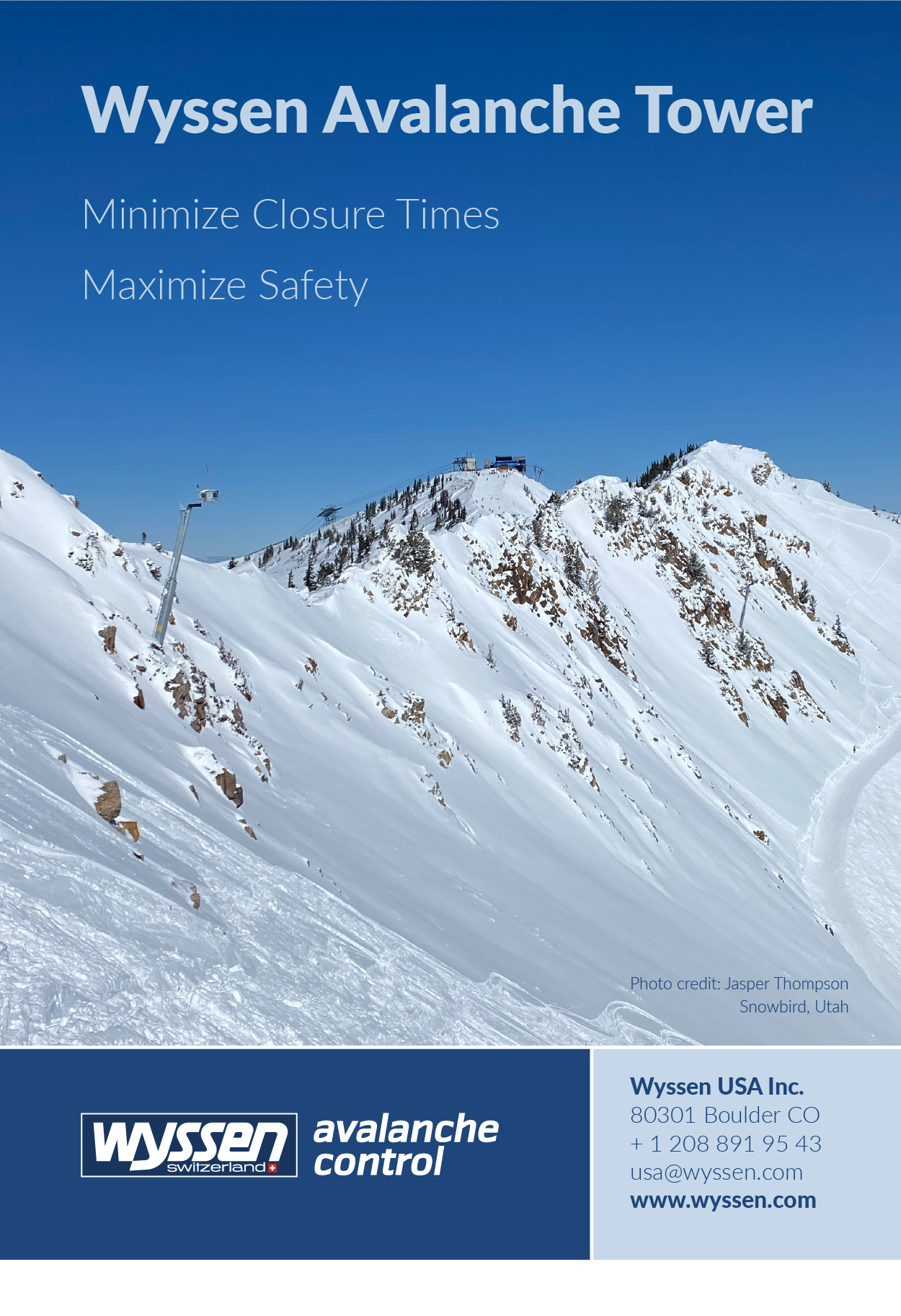

“Paul is in it!” in that delightful New Zealand accent was the last thing Vaughan said in his life. I still hear it with clarity in a repeatable loop with virtually no deviation even now, more than 33 years later. Paul was a tall, bearded Deadhead from New Orleans with big feet. His friends called him Hoofty Woofty, resembling Shaggy from the Scoobie Doo cartoon. I knew him as one of the many resort employees that gathered at the bar nearly every day about 4:30. Vaughan invited him to join us when we were in the employee locker room earlier that morning.

This is Vaughan Shelley, one of the victims, on the left, and myself on the right. I took this photo in January 1989, perhaps a month before the avalanche.

I reached with gloveless hands towards my ski poles to traverse out of the way, but never touched them. The shockwave of air blasted me downhill. It ejected me from my skis, left like dinner plates when the magician yanks a tablecloth. I would later see the same shade of bruising it caused along the entire right side of my body, clearly outlined at my ski-boot’s top and metal watch band.

The tumbling began. Complete lack of control from head to toe. Arms twirled and hands punched my face. Knees smashed against each other. My body was contorted and yanked in every direction. Every ligament strained. I’ve never considered myself particularly limber, regardless the heel of my right boot hit the back of my head.

Explosions of water and ice and everything in between. The detonations were more wet than solid; the energy inside so ferocious it had melted the medium. I instantly had no idea which way was up. Blasts mushroomed from every direction towards every direction across and through my body. Folks who study avalanches later told me the steep terrain would have propelled the slide well above 100 mph.

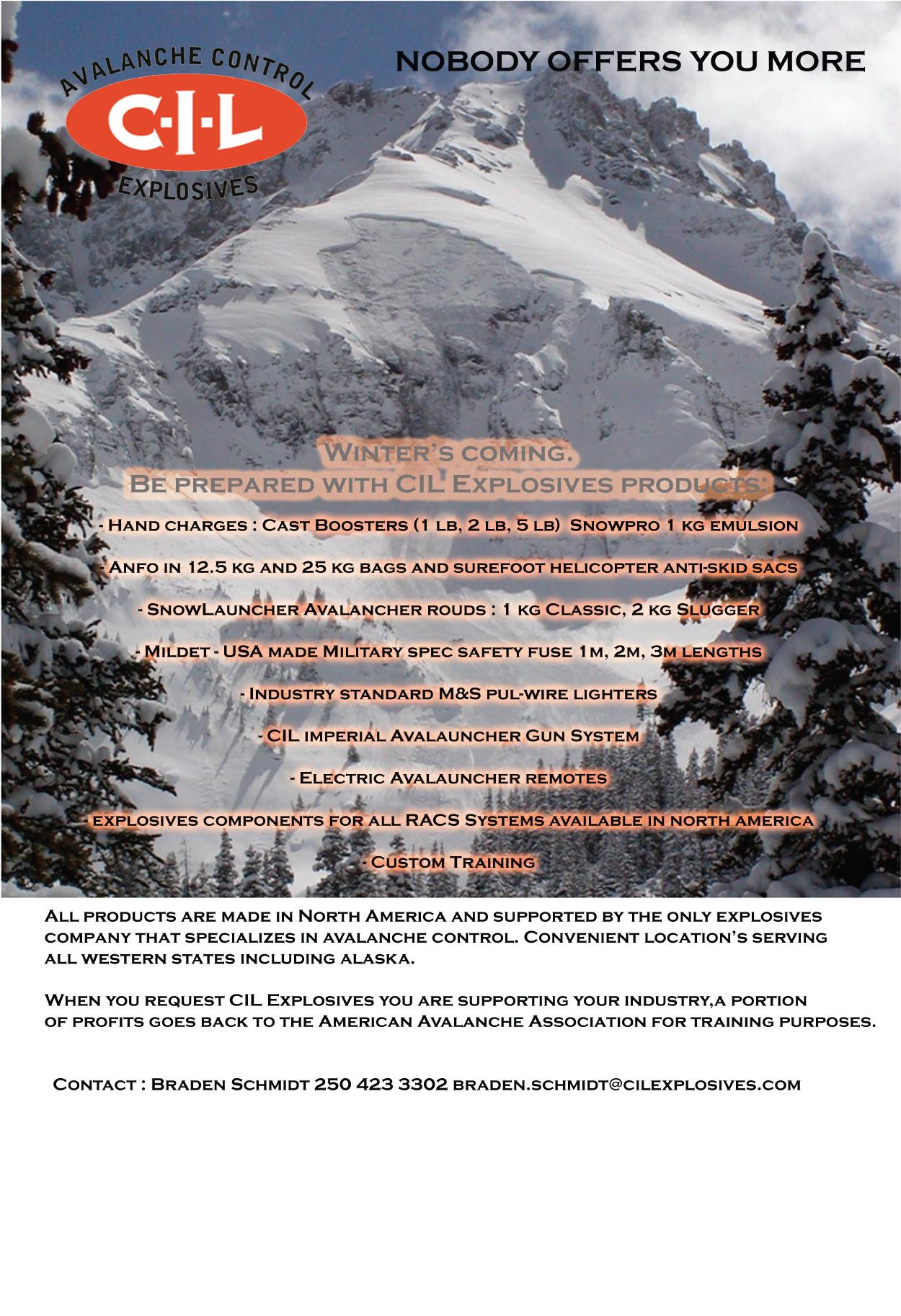

And then the unimaginable: the slope geography turned up the volume. Pressures increased as I entered the chute. Temptation, or as the locals call it Tempter, is a 2400’ vertical mountainside shaped like an hourglass—wide open terrain at the top and bottom, with the waist perhaps 800 feet long and narrow enough to not fit jump- turned skis much more than 200 cm in the early season or low snowfall years. When viewed from uphill, this V-shaped corridor was straight unless one counted the various rock formations protruding from either side.

We’d had snow that year but not copious amounts, and by my best guess, the narrowest opening was still less than 10 feet wide. Traveling at over 100 mph hoping to pass through a 2+ football-field-long corridor with rock walls forming a narrow passage without any control was the exact opposite of what I’d just performed flawlessly only seconds before. A desperate roll of the dice with nothing but death a probability instead of the perfectly controlled descent from years of accumulated skill.

Various forms of liquid and solid cannoned down my throat, stuffed into my sinuses, and packed under my eyelids, its penetrations powered by immense pressure. I mistakenly assumed my eardrums burst when my hearing suddenly vanished; later I discovered it was because snow was packed forcefully against my eardrums. Cold slop rushed up my pant legs and sleeves. Zippers popped; seams failed; clothing tore.

My left boot hit something that shattered two buckles and pinwheeled me inside Mother Nature’s Slush Puppy machine, a churning tumbling whirlpool of explosive activity beyond description. This was where both my companions died of massive injuries from multiple collisions. Neither survived the ride to the bottom. Both funerals had closed coffins.

I miraculously shot straight through the choke, but the violent tumbling continued. I was soaking wet as if I’d jumped fully clothed into the Arctic Ocean. I thought of the big waves I’d body surfed as a kid on Cape Cod with my cousin Barry. Before this day, I would have considered some of those wipe-outs ‘huge.’

The tumbling then unexpectedly stopped when a strange weightlessness began. The countless flakes of snow and drops of water paused their attack against me, instead falling alongside me. We were in laminar flow, directional unison, as we went over the cliff. This was good news; it meant the horrific ride would soon be over.

I’d never gone over the cliff, nobody ever had. Its 80-foot drop is at the very bottom of Temptation. Skiers avoided it by turning left and traversing through the trees to get to the bottom of the ravine. It was then just a gentle two-mile slide alongside Bear Creek Canyon to get back into the beautiful town.

But here I was going over it with a surprisingly soft landing and a sudden slowing of speed. I thrust my left hand to the direction of light. The lower levels of the snow stopped before the upper levels, so I slowly rotated to a stop, my left hand’s bare fingers on the snow’s surface. I was star-fished below, a frozen position of a mid-jumping-jack.

Here are two photos of Temptation after the avalanche. I took them from a helicopter. Vaughan’s father rented it and invited me, he wanted to see where the accident occurred. The photo below shows more-or-less the top of Temptation, the photo at right shows the choke.

I could not inhale. Slop filled my mouth, was well down my throat and packed up my nose. I chewed it, tried to swallow but could not, the passage blocked by just more of the same. It slowly melted against the walls of my esophagus. I swallowed hard and the large mass descend coldly into my belly. My eyes had a similar situation- snow packed under my eyelids. I squeezed them shut and felt the jagged crystals turn soft against my corneas and run like tears down my cheeks. Snow packed into my sinuses began to melt and run out my nose.

My airways were now clear, but I was still suffocating. Inhaling only brought more of the slush. I closed my mouth and tried to suck air through a sliver between my lips without success. Frozen particles went into my nose. I left my eyes open but could only see a blurry white. The cold crystals stung against my eyeballs.

My only chance was to dig down with my exposed left hand. It was remarkably difficult as I initially could not bend my arm. I articulated my wrist and rotated my arm like a tiny backhoe, digging out my arm with my arm. I could soon flex my elbow and dug downward towards my face with the sensation of drowning.

I brushed the mashed potatoes consistency from my mouth and nose. I swallowed, spit, coughed, snorted, and screamed in rapid repeated succession, the echoes bounced off the canyon walls. I was miraculously still alive and thought I would survive, hoping my companions would do the same.

After catching my breath I thought I could just pop out of the snow but immediately discovered there was nothing to push against, nothing to pull from. I was suspended, trapped, and aware that each exhalation of my rib cage allowed the pack to settle and sink just a little more, preventing each new inhalation from being as big as the previous one.

With one hand, I dug the snow from around my neck area and tossed it out of a funnel that began to form, exactly an arm’s length deep. I clawed with my knuckles because using fingers bent my nails backwards. My skin began to shred. It hurt but I didn’t slow; breathing was more important than skinned knuckles. The snow grew streaks of pink. The settling continued. My lower ribs pressed hard against the firm squeezing mold.

I learned at a young age that my lungs held more than average volume, benefits of my genetically large rib cage. It served me well now. I inhaled as much as I could to resist the squeeze of the settling, trying to never fully exhale, a rapid succession of taking air in, and only exhaling until I felt the medium settle more.

In a short time the upper section of my front chest was exposed, allowing near normal breathing. I screamed for help a number of times but heard only my own echoes. I yelled my companions’ names but neither answered back. A horrible thought crossed my mind: that they could both hear me, but only because they were both buried beneath me.

I started shivering which quickly grew in intensity. Prior to this moment, I would describe shivering as a fairly mild internal reaction, but now it radiated outwards. My arms shook and my legs quaked inside their molds. My hair, once wet, was now frozen in place against my scalp. No matter, there was only one thing to do: scrape, scoop, toss, repeat. I learned that a quaking single hand can toss a remarkably small amount of snow.

I dug towards my right hand which was outstretched perpendicular. Scrape, scoop, throw, even though most of it didn’t clear the rim of a funnel I was quickly forming. If I didn’t toss the small handful far enough it just tumbled back to where it originated. I tried tossing it behind me only to have it fall down the back of my neck. The sun was warm on my face, but my teeth rattled uncontrollably. I kept inadvertently biting my tongue and tasted blood.

Thinking it would be my ticket to an easy escape, I continued digging towards my right hand. After perhaps 30 minutes, I moved enough snow from my right shoulder and biceps area to free my arm. I gasped with joy convinced I would exit in moments as I now had both arms to push with. I eagerly planted them on the bottom of the funnel now below my armpits and pushed.

Nothing.

Initially I was not disappointed in the complete failure; clearly I had not taken the effort very seriously. I thought of Olympic weightlifters; they don’t just walk up to the bar and heave. They inhale and exhale, concentrate, and give a pause before focusing their huge effort. I smoothed an area under my armpits flat and level, I planted my elbows into the wall behind me and spread my hands against the groomed cold lower surface. I closed my eyes, concentrated, took several deep breaths, and mentally counted to 3 before pushing downward with shoulders, arms, hands, and everything in between. The strain was lengthy and fierce; the most force in a single direction I had ever generated. It sent my head spinning, my closed eyes saw stars. I’m sure my face was dark red.

Nothing. I didn’t move a single millimeter.

My ski boots were anchors. The tops of my feet locked me in place. If I could somehow remove my feet, my legs could slip upwards. Once proud of how stiff and articulated my custom-fitted orange Lange boots were, I now cursed them for not being bedroom slippers.

I kept digging with both hands and figured if I could dig down far enough I would be released. Scrape, scoop, toss, repeat. My funnel’s walls were too steep, the deeper I dug, the more snow tum- bled in. I reached to the rim and increased the circumference. I dug down more but only another inch before having to again widen the circumference of the rim. It was a maddening function of the medium’s instability. It seemed I had to move every ounce at least twice. I’d already been there over an hour. The shivering grew intensely.

My body temperature, the shivering, and wet but now re-freezing snow had formed a shell around me—a continuous hard surface ¼ inch from my exterior. It felt smooth and polished against my knees, hips, and bottom. I thought of the ‘chair’ I frequently made along my parents’ driveway after shoveling a New England storm. I would jump backwards into the snowbank to form a perfectly-shaped recliner, comfortable as it was formed by my body. I remember even closing my eyes to enjoy the warm winter’s sun.

Then I woke up.

Still in my funnel. Like falling asleep while watching TV, I could pinpoint the second I wakened, but exactly when I dozed off was a mystery. I went back to digging but with ferocity, I feared hypothermia was setting in. I could fend it off only with faster movements. I screamed a few more times.

By now the funnel’s floor was just below my rib cage, but well above my belly button. The water created by the snowmelt during the slide had trickled downward and re-frozen. The deeper I dug, the firmer the cement was. I was no longer scraping snow; it was more a form of ice. My knuckles could do little against its hard structure. I punched it with bare fists to break it, then scooped and tossed the fragments.

The shivering had slowed and eventually stopped. At the time I thought my more-aggressive movements had somewhat warmed me, but eventually the dismal thought of severe hypothermia set in. I couldn’t feel my arms past the elbows or legs past the knees. My body was sacrificing its extremities by constricting veins to save the remaining warm blood for vital organs.

My hands had balled into fists. I pried fingers open with my mouth, but they snapped shut like a sprung door hinge. I could still scrape, but fisted hands couldn’t effectively scoop or toss. I removed my season/employee pass from around my neck. The credit-card-sized laminated badge now became the smallest snow shovel in recorded history. Punch, scoop, throw, repeat, one teaspoon at a time.

I missed the ability to extend my fingers, nothing I considered important until now. I thought of President Nixon when he finally left office in the Watergate years, saluting double peace signs when he last boarded the helicopter.

I woke up again.

Losing consciousness twice was an ominous indicator. Falling asleep during this truly desperate time seemed incredibly lazy. Would I wake if there was a third? I’d read about climbers on Mount Everest who sat down never to rise again, despite others pleading with them to get up, they rarely would or could, claiming they just had to rest a few more minutes to gather strength—a horrific unknowing slow path towards certain death. Many of them are now ominous permanent fixtures on the mountain. I understood them now. Despite the obvious need to work hard and fast, my body told myself only to stop and rest, to gather needed strength. I’ve been stuck for approximately 90 minutes.

I woke up again.

My balled fists now curled inwards and my biceps remained strangely flexed resembling a praying mantis insect. It was difficult to even hold my season pass let alone maneuver it correctly to toss impossibly small amounts of snow. I couldn’t straighten my arms, so I could no longer reach the top of my funnel. My arms felt as useless as those on a Tyrannosaurus rex. My legs were equally trying to fold. My knees pressed forward. My body was coiling.

I thought of my parents, how eternally sad they would be. I wanted them to know that it was my own stupid fault, no blame placed on any other shoulders, and dying this way did not hurt. Hypothermia was merely shivering followed by a nap, a gracious way to go. To this day if given the choice I would choose hypothermia as a way to die.

I thought of my friends in the Telluride Ski School, how this would help educate them of the dangers. I hoped my buddies back at Sugarloaf Ski School would raise a Ballentine for me at The Bag on a Saturday around 4:30.

I wondered how long it would be until, or even if, my body would be found. I hoped soon so the visual would not be painful for anybody. A week in this cold would preserve me well, but if it were months or years, the scene would be very different. I mentally apologized to whoever it would be.

Will animals eat me? Are there vultures at this altitude? I knew they went first for accessible soft tissue: my eyeballs. Could they be removed if the liquid inside had frozen into solid spheres? Perhaps they would go for my tongue instead. They would certainly skip my fingers, even though they were covered in blood, as they were already cold and rock-hard.

I pinched my season pass with the backside of my balled fists and clumsily put it back around my neck for easier identification. I didn’t voluntarily close my eyes, but assume it was a short time before I again lost consciousness.

Around this time two thousand miles away both my mother and sister experienced a strange phenomenon. My sister, an actor, had just finished an audition when she suddenly broke down in tears. Unable to explain why, she later described it as a sorrow-filled sense of complete doom. My mother, walking quickly between airline flights in a crowded airport, paused to pick up a penny ‘for good luck’ though she’d rarely done it before, made more difficult with her arms full of luggage.

Meanwhile, my eyes were closed, but I had no strength to open them. I was shutting down, literally. A sensation of getting smaller. A campfire flame running out of wood. A shrinking ice cube in hot water. I was retreating from this world towards an enormous void that was simultaneously inward and outward. My perimeter both dissolving and becoming the lifeless abyss around me. Vacant of boundaries or direction, it was truly nothing but was enveloping me. A darkness without color or texture. It had no end and no beginning. It was lightless, soundless, and place- less, and yet it reached beyond the three dimensions. I was taking the journey, though I had no control of it.

“That was awesome,” I heard, quite clearly. Skiers. Other backcountry skiers were nearby.

I yelled, but no sound came out. I tried again but nothing happened. My physical body long shut down though my thoughts still very active. I heard the clink of ski poles. Scream. Groan. Something. Anything. I tried to wake but could not, my inside banging against my outside, my tiny soul hitting the cold still walls of my exterior. An internal war between eternal sleep and life.

I had, so far, survived a series of one-in-one- thousand events, all for nothing unless I could take advantage of this last tiny sliver of good fortune. I’d beaten all the odds in the Grim Reaper’s Casino only to fall asleep before cashing-out and leaving to celebrate. A ski patroller later told me being hit by the avalanche alone could have killed me. Rocketing through the chute with only the loss of boot buckles was an incalculably small possibility—both Vaughan and Paul ricocheted off the walls and had massive head trauma. Being buried relatively close to the surface and upright…close enough I could thrust my hand to the top was a very lucky thing. My companions were later found by a cadaver dog buried more than 12 feet deep.

Regardless now, my would-be rescuers were close by with me not being able to contact them. My soul shook. I internally lashed outwards, battling against the closing down of my senses, my systems, my body itself. It seemed impossible. Pushing huge logs against a swift current, nailing jello to a wall.

This was, by far, the scariest moment. Worse than being hit, carried, or buried by the avalanche by a very large margin. 33+ years later I still have the same horrific dream whereby I understand I am asleep, but I cannot jolt myself awake and it feels as if I never will. This dream comes to me several times almost every year around early February, and it always ends the same way- my silent scream slowly creeps to the surface and turns into a wild yell that awakes both me and everybody in the house. Nothing on that day was scarier. No other event brings me a sense of dread like those last few moments. I was physically well into the process of dying, and yet part of me was very much alive and fighting, though so far, failing. My thoughts were firing red hot while my limbs were frozen logs.

And then it finally happened. I don’t know why, I can’t describe the path, but the connection between my thoughts and body finally occurred. Light sensed as my eyes opened simultaneously with my mouth. Out came undoubtedly the loudest and longest sound I’ve ever made. A wild rabid moan of countless vowels varying in pitch that stopped only when there was no more air in my chest to propel it. The echoes bounced off the walls of the Bear Creek canyon. I listened for a reply. Was I already too late? Had they already left? Desperate for a response. This was it. If a human responded, I would live, if not I would die. Period.

“Where are you?” I heard in a speaking, not yelling voice that was clearly very close by. The volume changed as if the person was rotating their head as they spoke.

“HERE!” I yelled in a voice that cracked mid-way. I tried throwing any ounce of snow from my hole. The paired click sound of ski bindings being released and stomping feet approached. “Jesus,” he said while peering over the rim of my funnel. I was blue.

AFTERWARDS

Physically, I was a wreck for many months. I was lucky to not lose any fingers from frostbite, and the skin I tore from my knuckles when digging eventually grew back, though the scars are still very prominent. But for a long time, everything just hurt. All my joints and ligaments were strained from the ride. It took a few weeks before I could comfortably walk and doing anything requiring coordination was absolutely out of the question.

Mentally of course things were much worse. I saw a therapist less than three months after the accident, and only now I know that I quit very quickly because I was just too scared to discuss it, the emotions were overwhelming.

In the summer of ’89, five months after the slide, I was more or less living on my parent’s couch, sleeping late, eating a lot and drinking even more. I spent the day watching TV where I discovered NBC sports coverage of the ’89 Tour de France. I learned of Greg LeMond’s near-death experience from being shot by his brother-in-law when turkey hunting, and literally cried like a baby when he won the three-week race by just eight seconds. He proved to me that anything is possible if I truly wanted to do it. I got off the couch and bought a bike the next day. I trained hard and years later won a few bike races myself. I still ride to this day.

One of the more difficult aspects of the accident was the admission to myself that I was the better skier of the three of us, and though I certainly did not have a lot of experience in the backcountry, my companions had even less. I was certainly not ‘the leader,’ and it was not my sole decision to ski there that day. Vaughan had skied Temptation Chute the day before, and we’d shared a beer soon after it and planned to go the next day. I honestly don’t remember how Paul ended up joining us, and I didn’t know him very well. Regardless, as a ski instructor (on my day off) many of the locals were angry and quite vocal that I had somehow been the principal of our group, and it was my fault that the accident occurred.

It didn’t help that the Colorado State DA contemplated pressing two charges of involuntary manslaughter. If found guilty I could easily spend the rest of my life behind bars. I appeared in court in Gunnison for the charges of Federal Trespassing. I plead guilty and offered to the court my hopes to work with local schools and the U.S. Forest Service to help educate. I ended up traveling to Denver and sat for a video recording to tell my story. The film was later edited and distributed to many ski areas who used it to train employees before each ski season. To this day I have friends who are forced to watch it each year. I’d taught skiing at Sugarloaf in Maine before I moved to Telluride and returned to Sugarloaf to teach again. It was good, my friends understood what I’d been through and were supportive of me coming back to the sport. I eventually moved away from Alpine and into Telemark as a new challenge, and even made it up the PSIA ladder to become a Telemark Examiner.

Perhaps 15 years after the accident I found myself growing increasingly depressed each winter as the anniversary (Valentine’s Day) approached. I finally got the courage to find a therapist. At the time a new method of treating PTSD was coming out called EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing). In a nutshell, the therapist asked me a series of questions that when I answered were always somewhat negative. Example: “Of the three of you, who was most at fault for the accident?” was always answered with a tearful “me.” Then the therapist performed a rhythmic tapping on my knees (while seated) and asked the same question. It is a strange format whereby the input of the knee tapping occupies a part of your mind so the other part can contemplate the question without just falling into the same repetitive rut it previously had. When she asked, “Of the three of you, who was the most at fault for the accident?” I started to giggle with joy, finally able to honestly say “nobody, we all made the same exact mistake.”

Above all perhaps the most important lesson I learned is the old saying ‘Hindsight is 20/20’ is completely false. Looking back in time does not give a clearer understanding, it only skews and distorts and results in ‘what ifing’ yourself literally into a form of insanity. I’ve tried to teach this aspect to dozens of people I’ve met over the years who have done something that resulted in injury or even death to others. I feel it’s the best I can do to relieve their pain. ⬢

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Todd Richards now lives in Bristol, Maine, married for 27 years to his wife Sarah, where they own a small gallery and run a website of his wife’s art (SarahRichards.com) Their 20-year-old son Sam goes to Brandeis University.

HEADER PHOTO: Nick Digiacomo