By Dave Richards

Disclaimer: I am not a formal avalanche educator. I have over the years taken the classes. But most of what I have learned is from working as a ski patroller. I worked under some excellent mentors, and of course learned from lessons in poor judgment (both mine and others’).

As the director of the avalanche program at Alta Ski Area I’m now in the position of teaching up-and-coming avalanche workers. I also find myself frequently looking back on my experiences picking up the pieces from avalanche accidents. When I do this I constantly wonder: what can we learn? Plenty.

When I first started to dwell on this piece of rambling thought, I had just finished reading an article in TAR 37.1. In it, two skiers told a story of their experience with an avalanche on a photoshoot on Mount Bachelor. The article is interesting in that it discusses some potential lessons from the event. However, as you near the end of the piece you are confronted with take-home points in yellow highlight. None of these take-home points are about mistakes or lessons learned! All the points are about what they did right. Why? They unintentionally triggered an avalanche. Something went wrong, where is the story about that in yellow highlighter? This is a common theme. Did they learn anything?

As I read stories like this from newer backcountry users, I often hear tales of greatness. How they read the forecast, checked the beacons, dug ONE hole and ripped. They are surprised when they trigger an avalanche. Nonetheless, they write up the event and usually the emphasis is on what they did right. Again, no, you unintentionally triggered a backcountry avalanche! Some would say that the only people who should ever trigger an avalanche are professional avalanche workers. Well, yes probably. It is the job of a ski patroller to be an avalanche hunter. A backcountry skier must be an avalanche avoider at all costs. This is hard to express to the backcountry user who just watched a movie showing their heroes skiing away from an Alaskan avalanche unscathed.

It is certain that the number of backcountry users is growing at an enormous rate. And admittedly but perhaps more interestingly the number of FATALITIES has not matched that growth. However, we are seeing an enormous number of close calls and partner rescues. And these numbers do seem to be growing. I would say that, although we should celebrate survival, we need to bring home a set of important lessons.

These close calls indicate that the industry has done an excellent job of training janitors who are able to clean up the mess. But it hasn’t prepared people to avoid making messes in the first place. Eventually the accident gets messy enough that no beacon skills can clean it up.

The Avalanche Education Experience

Current avalanche education is excellent, but we have the entry level wrong. We are creating skiers who think if you have the gear and know how to use it, you’re qualified to just head on out. I would say that they are not. A beacon is just a worthless computer strapped to your chest when you are beaten to death by the trees. Avalanche education does not properly convey the trauma and seriousness of avalanches.

When first researching this, I had an email discussion with my friend Sarah Carpenter, American Avalanche Institute owner/educator. The first thing that Sarah sent me was the curriculum for the level one recreation and pro courses. One thing immediately struck me. Although it’s true that the first lesson in every course is beacon skills and often a beacon test, against my suspicions there was substantially more emphasis on terrain and travel than there was on rescue. Amazing! This is what I have always wanted to see. I have ranted many times that we were teaching the skills backwards. It should always be to stay out of the avalanche first and rescue as a last resort second. Hard to do, I know, but critical so as not to teach a false sense of safety.

This left me with a conundrum; if Sarah was teaching the right information in the right sequence then why are people making the wrong decisions? Reality…I understand that when in the mountains, it is impossible to accurately read clues all the time. There is no question that avalanche events can and will happen.

Then the question became, why are people proudly telling us about their avalanche education at the same time as they are telling us about getting caught in avalanches? Are we teaching them the wrong thing? In fact, research has shown a correlated risk exposure with the attainment of avalanche education (McCammon, 2000, 2004).

Are We Inadvertently Teaching Confidence Over Competence?

One thing I think is flawed in our avalanche education is that we aren’t teaching young people the basic human skill of reflecting on their experiences. Being a mentor is not just teaching snow and weather. It is also teaching more basic human behaviors such as reflection and humility. These are traits that are becoming less common in the era of social media and instant gratification.

In the modern era I’ve encountered a different mentality which says that surviving a high-risk event is cool. In social media, scary stories make for more likes and more glad you’re ok comments. Praises and platitudes make it harder to look back and really analyze the event, examining where we went wrong and learning to avoid that same pattern or sequence in the future. We must teach people to spend as much time analyzing what went wrong as we do what went right. It is only through this that we can improve in the future. This is the very basis of learning, tomorrow’s forecast must include the lessons from today’s experiences.

Does the level one student need to know avalanche mechanics and the nitty gritty of snow metamorphism? My feeling is that the answer is no. This level of backcountry user only truly needs one skill: to be observant. If you keep your eyes wide, the mountains will frequently tell you all you need to know. In fact, evidence shows that the student of basic avalanche education gains a level of confidence. But at the same time they report a breakdown between the ability to grasp information and the ability to transform that information into actionable knowledge (Balent et. al. 2018).

Translating Theory to Action

Often, we see people ignoring a vast amount of information and operating instead on just one tiny bit while rushing out the door to beat the hoards. Every morning you give them what they need to know. How do we make sure they are getting it all? Can we teach them to apply the data available to them? How can we help people become responsible mountain users as opposed to relying on the wisdom of the “all-knowing” forecast center? We constantly throw around the term “Expert Halo” in avalanche education, this may be the most glaring example of that heuristic trap. There is much more to an avalanche forecast than the colors on the hazard rose. People must read between the lines and actually grasp the information.

Since it seems that we may be missing something in avalanche education, perhaps we should dumb it down to the simplest form. We need to take our recreational user education back down to the basics. In my experience with forecasting and in discussions with other forecasters much more experienced than myself, it seems that the more one sees and learns, the more they simplify their thought processes.

As one of my mentors, Titus Case, brought to my attention, we need to focus on the low entropy data spaces that Ed LaChapelle addressed so eloquently in his 1980 paper The Fundamental Process in Conventional Avalanche Forecasting (Journal of Glaciology, vol. 26, no. 94, 1980). In information theory, entropy is a measure of the uncertainty associated with a random variable. Therefore, the concept of thinking in a low entropy data space is that of working with known variables or in less uncertain spaces. What DO I know?

When needing to acquire knowledge about a new situation, an experienced forecaster immediately starts asking questions in low entropy data spaces. The inexperienced person often attacks complex relations of snow and weather and ends up awash in a sea of information. The key first question does not deal with last week’s range of snow cover temperature gradients or yesterday’s sequence of freeze-thaw crust formations, but simply asks “Has an avalanche fallen recently?” (LaChapelle 1980)

In truth you don’t need to dig a pit once you know the basic stratigraphy of the snowpack. And this structure is information that the lay user can easily glean from their local avalanche center. Once armed with this knowledge a quick hand shear or simple step off the skin track often tells you much of what you need to know. Then by simply looking around for those other obvious signs such as recent avalanches one can most times complete the puzzle.

The Student

To be clear, I am not attacking students of the formalized avalanche education process. All of us who go to the mountains are students. I believe that the onus is on all of us to be constantly learning from the mountains and analyzing our experiences of both success and perhaps more importantly failure. The student most often simply doesn’t know what to look for.

The problem is not with the incompetent. The incompetent don’t know. As a result they often don’t go just on the basic knowledge that they glean from an avalanche forecast.

It is instead those people whom we have begun to teach, the people who have proudly completed their first avalanche class, that are most dangerous. We may have armed them with a confidence in their knowledge that far outweighs their ability to apply the skills they have learned. They have just enough knowledge to kill themselves.

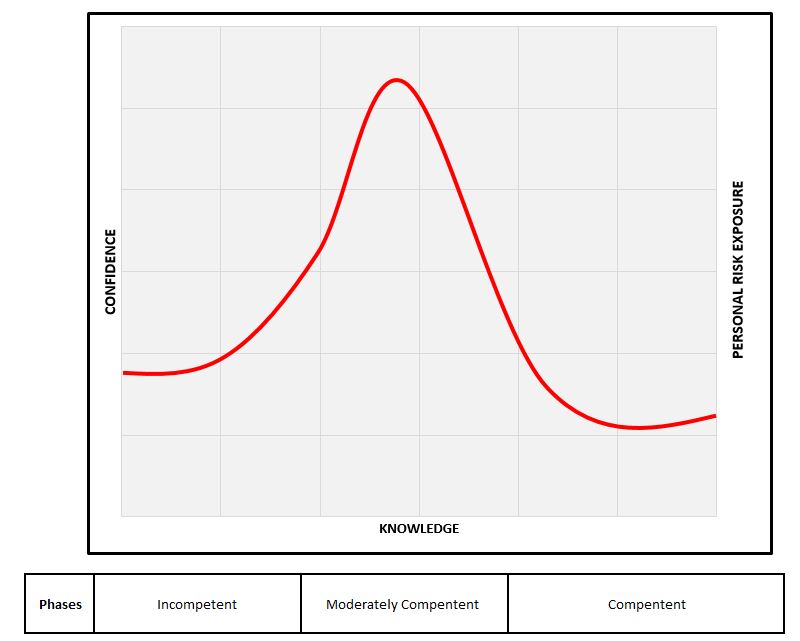

These are the people Bruce Kay describes right off the bat in his book Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose in the Avalanche Patch when he discusses the Dunning-Kruger effect. This study from David Dunning and Justin Kruger from the Cornell University Department of Psychology found that there are three types of decision-makers (Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, vol. 44, 2011.) that we can apply to the students of avalanche training.

- The “truly incompetent” may tend to overestimate their knowledge and skill, but luckily for them these people also frequently recognize that they don’t really know anything.

- The “moderately competent” who will tend to overestimate their knowledge, skill and ability resulting in over confidence. These are the people that Kay describes as suffering from “level one disease.” This description couldn’t be more accurate. I think of these people as being dangerous simply because they don’t know what they don’t know. Yet unfortunately, they think they do.

- The “most competent” will tend to underestimate their skill, knowledge and ability leading to less confidence than justified. Unknowingly through their humility and lack of confidence which comes from a lifetime of developing experiential expertise these people make conservative decisions.

In my mind these are the long-time avalanche professionals. They still don’t know what they don’t know, but luckily most at least know that.

This graph depicts these users and decision makers. (Because really, what piece of bad writing doesn’t need a graph?)

Although this graph is simply a representation of my thought, it seems to be awfully accurate for this situation. Of note are the phases of competence listed at bottom. The further one progresses toward competence or expertise, the less they think they know. It is in the center, where the individual is in the zone of the “moderately competent” where they become overly confident, and as a result increase their exposure. This is where bad things happen. These are my overly confident users who are not accurately analyzing either what they have been taught or what they could have learned.

A highly valid learning environment (Kahneman and Klein, American Psychologist, vol. 64, no. 6, 2009) is available in avalanche events. Kahneman and Klein say that two conditions are necessary for the skill development: high-validity environments and an adequate opportunity to learn them. When you trigger an avalanche, either intentionally or not, you are being handed highly valid information. This is direct feedback as to the accuracy of your snow assessment and decision-making: what many people call bulls-eye information. Here is an opportunity for a learning experience through which expertise is eventually developed, as long as the experience is properly debriefed or analyzed for its lessons.

Meanwhile, when one skis a slope but there is no avalanche, this does not qualify as a valid environment. This information is inconclusive. Yes, you may have been right about the snow stability for sure, but you may also have been lucky. Nothing happened so you’ll never know. It is in these learning experiences that much can be learned. As opposed to writing a tale of victory, in a close call we must write a tale of defeat and an analysis of what can be learned.

Based on my observations I believe that our “moderately competent” skier, the one with “level one disease,” is understanding and analyzing these learning opportunities in reverse. They are taking more information from the non-event than from the close call.

The Teacher

So, where does this whole thing leave us? I feel as much like a parent as a mentor or teacher in the avalanche industry. The only problem is I’m not a parent, I have no desire to be a parent nor do I have any experience in this realm. Between my parents and mentorship over the years from other forecasters such as Titus Case and Liam Fitzgerald, humility was one of the most valuable lessons I learned in the avalanche world. The other lesson learned was the most basic skill of simply being observant. We can’t outthink the avalanche and will never completely control the avalanche danger.

I also learned the importance of taking responsibility for my actions. The rest of the equation must come from lessons learned, whether those lessons are the brutal truths of losing friends or they stem from close calls due to poor judgment.

It is time for us to stop training avalanche safety and start teaching. Along with beacon, shovel, probe, we must add brain. Perhaps it is about parenting—teaching to avoid the fight at all costs instead of how to bandage after we get our asses kicked.