What Affects Your Decision-Making?

By Ken Wylie

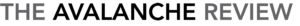

Over the last ten years there have been fantastic advances in the field of avalanche safety through research and technical development. Additions made to snow stability evaluations, terrain assessment tools and avalanche response technologies deepen our awareness of the snowpack, our decision-making skills and our response times. Yet when I look at these intense efforts, it frustrates me that people are still dying out there each winter. Even some of the best: Robson Gmoser. How do we make ourselves safer?

Ian McCammon’s work with heuristic traps is helpful. He discusses how decision-making shortcuts work against us, like familiarity. As if a past experience will predict a future one. Or by seeking acceptance from others socially, yet not sharing what we know to be true for ourselves. Great steps toward the notion that our decisions are often flawed, but I propose that we go deeper and come to better know our situation inside.

Casting light on our character flaws frightens most human beings. In our industry, my observation is that we try to replace looking at ourselves with technical solutions. If Icarus (from Greek mythology) was plummeting to the sea, (and he was an avalanche professional), he’d say: “Daedalus should have used epoxy to glue the feathers to these wings instead of wax.” When really the lesson was about hubris. When tragedy strikes, we often point to and wonder about technically obvious factors that were ignored, and we ask: Why?

In Transforming Your Dragons, Dr. Jose Stevens lays out seven archetypes that can afflict humans. His work is a powerful tool for putting language to our internal situational awareness in a way that we can easily identify in our decision-making, if not fully admit to recognizing in ourselves.

- Arrogance

- Self-Deprecation

- Impatience

- Martyrdom

- Greed

- Self-Destruction

- Stubbornness

According to Stevens, each of us is particularly plagued by one of these seven dragons and they surface, or gain control, in the presence of fear. However, it is also important to keep all of them in our awareness in the decision-making process. Let’s take a closer look at each one of these and see how they can play out in the backcountry skiing paradigm.

Arrogance

There is a big difference between confidence and arrogance. A confident winter backcountry guide or enthusiast also listens to input. There is a willingness on the part of the confident individual to welcome new information from anyone in the group. Conversely, a person with the arrogance dragon will say, “I am/know the best,” and believe it. This individual is incapable of receiving input from others. The root of this behavior is insecurity. Arrogance in avalanche terrain can and does lead to information gaps. Individuals have blind spots, a limited perspective grounded in biases and perceptions. If we invite others into the decision-making process, the scope of available information broadens, which can impart the choices we make.

Self-Deprecation

Self-deprecation is a lack of confidence to the point that we forfeit our voice. We may possess the most relevant piece of information, but we are too afraid to share it because we carry no value in our perceptions. If we consider that all parties exposed to the hazard of an avalanche are risking the same thing—their life—then we need to master social courage and speak up.

Impatience

People with the impatience dragon are stricken with the fear that if things are not happening quickly, something bad will happen. However, being in a hurry can lead to a failure to take the required time to do a task safely and efficiently. In the mountains there are many instances when going more slowly can help us maintain a higher level of diligence and therefore safety. Think of crossing an avalanche slope one at a time. It can be uncomfortable to travel slowly if we fear worsening conditions, but only time will tell if the conditions worsen. Rather than rush through a critical piece of terrain, explore other options and terrain choices.

Martyrdom

Martyrs are victims; they feel that they do not have the power of choice. Others make decisions for them and they are oppressed. This differs from self-deprecation in that martyrs have good ideas, but they are not heard or heeded by colleagues or friends. A martyr follows a leader onto a suspect slope, despite knowing the potential consequences of withholding their knowledge and information. We say, “Oh, I don’t think this is okay, but they want to go there, so I guess I’ll go with the flow. I don’t want to make waves.” In this case, the fear is about standing in one’s truth and living it to the full, regardless of social fallout.

Greed

Greed is an easy dragon to understand, especially on a powder day when the sun is shining. The statistical fact that more avalanche tragedies happen on sunny days with new snow underpins the concept of greed. After a long period without any snow it becomes more likely that we may undermine our own ability to make rational decisions, making going for it easier and escalating our tolerance for risk. Our greed dragon also comes into play when we race ahead of other groups in order to get first tracks. Our focus on the race can erode good decision-making.

Self-Destruction

Self-destruction may be fueled by a general propensity for self-hate, depression, or a sense of despair. This does not make for good decisions in avalanche terrain. It brings a devil may care attitude to an activity that requires great care and diligence to preserve the well-being of self and others. This behavior often creates drama and subconsciously encourages poor outcomes. The underlying fear is one of success and the responsibility that it brings.

Ironically, these individuals may have a long list of successes in the mountains, but the intention behind those successes is suspect. Were they reckless and lucky? Stubbornness. When afflicted by the stubbornness dragon, we refuse to cooperate. It may be that we are afraid to be wrong, or we are so fixed on the objective of the day that we can’t shake ourselves from achieving the goal. Single mindedness can be a required strength in hazardous environments, but the game is about seeking the best solution to the challenges we face.

Fear fuels these archetypes. Be it the fear of not being as good as we claim, our own self-efficacy, not enough time, personal responsibility or simply being incorrect, each of these fears is a hazard to the avalanche professional, as it is to human beings traversing through life. I believe I have been gripped by every one of these dragons at one time or another. However, mostly I have tripped on being a victim to others: martyrdom. What I can do to remedy my fear is to be aware of it.

There is a place for fear in the avalanche game. Fear keeps us on our toes and brings focus to hazardous situations. In the case of tragedies, rather than point out what appear as obvious flaws, let’s instead try to understand what lead to the mistake. Let’s identify that process within ourselves. That is the cure for fear of any unknown: facing it with full situational awareness.