34 years ago, a monumental avalanche wrote a tragic chapter in Aspen history

Editor’s Note: I received a link to this story from Rod Newcomb, saying that it was “a fantastic story with a message.” When I was able to procure the text and photos for this TAR, he added, “Splendid. I knew Snyder, Kessler, and Soddy from the early pro courses in Jackson. I recall that they liked to party at night. The avalanche in Highland Bowl cut to the core of every snow safety patroller working at the time.” ––Lynne Wolfe, Issue 37.1

By Tim Cooney, Aspen Journalism

What many Highland Bowl lap counters and sixth-gear cruisers now take for granted as an everyday occurrence is only possible because of the sacrifices made by a distinguished lineage of Bowl-focused snow experts on the Aspen Highlands Ski Patrol going back to the 1970s. To this day, they put their skin in the game to tame what was once thought to be an unmanageable ski wilderness.

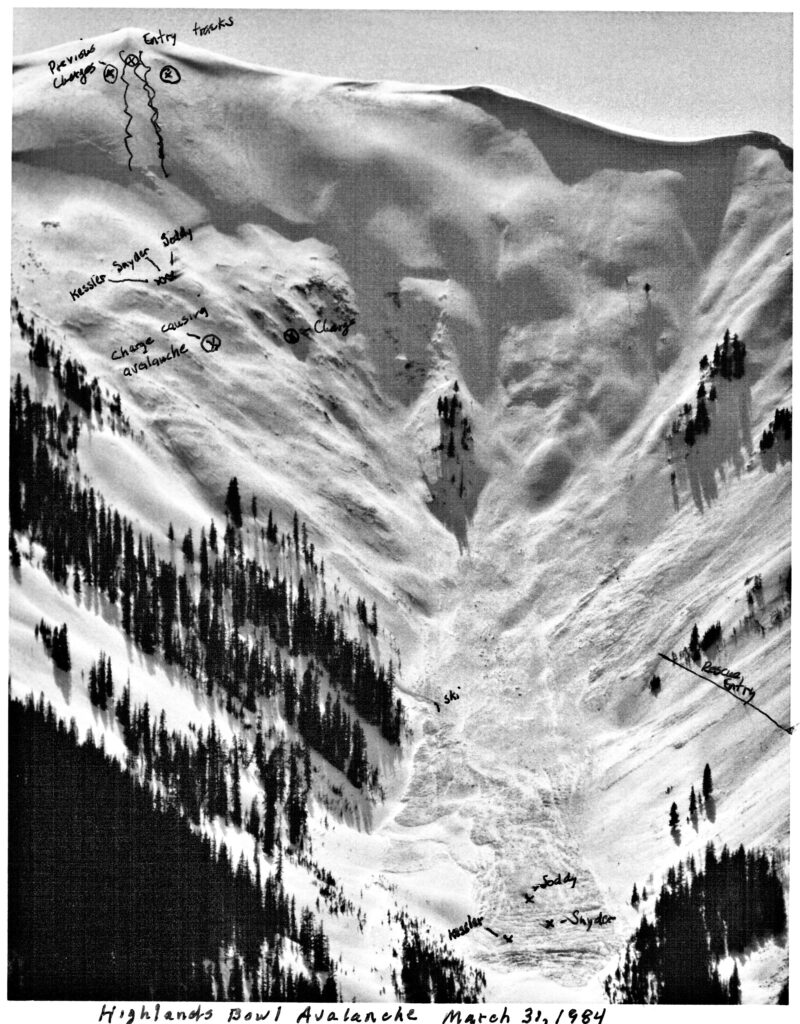

One event stands out in Bowl history: an avalanche on March 31, 1984, that took the lives of three ski patrolmen. The day began in Aspen with temperatures in the mid-30s, as fanciful clouds scudded across a deep blue Colorado sky, with no hint of imminent tragedy. At 11 a.m., “4-7 Control Team” consisting of Tom Snyder, Craig Soddy, and Chris Kessler left Loge patrol room to hike the bowl and do snow safety work. After launching a number of two-pound charges off the Highland Bowl ridge leading to Highland Peak, they skied down between the resultant craters in upper G-8, before stopping at the North Woods edge one-third of the way down, one eyewitness said. Eyeing their objective in the lower-middle section of the Bowl, they consulted.

Their confidence was based on historic Highlands documents of snowpit analysis, the strategic placement and some deep burying of nearly 200 charges in upper Bowl starting zones throughout the 1983-‘84 season, and a remarkably cohesive upper Bowl snowpack that had defied season-long efforts to shake it loose. One by one they traversed to the skiers’ right-center bench of G-8, deep in the tangible sacredness that Bowl travelers of all eras know well. There they deployed a launcher dubbed “The Ultimate Weapon,” an effective device that sling-shot charges into places too far to otherwise reach. They planned to put three more charges into a refilled lower pocket that had slid on March 8 and twice in December (the first slide in early December was naturally triggered).

The first charge to the skier’s left in lower B-1 (now between lower Ozone and Be One) brought no result. Then they launched the second of the charges below them where the pitch steepened. They never got to launch the third. What happened and why has become a lookback topic of armchair quarterbacking. But examination of original Highlands snow safety and ski patrol records from that time and interviews with at least a dozen individuals with knowledge of these matters add much more to the story.

Men of the patrol

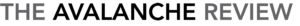

For those who don’t know and for those who may remember, Snyder, 35, Soddy, 29, and Kessler, 27, were three devoted ski patrolmen in the prime of life. Memory of them deserves a nudge, especially if one passes by the plaque that bears their names near the top of the Loge lift.

Tom Snyder “was up there every day with a magnifying glass,” said then-assistant patrol director John “J.R.” Rupinski. After studying at avalanche schools in Alta and Jackson Hole, Snyder took to being one of the first Bowl snow-safety leaders. As an early student of the morphing snow layers and hidden shear surfaces in the Bowl, he helped establish a foundation of knowledge that underlies Bowl understanding today.

Snyder lived in his van in the Highlands parking lot, which Whipple Jones, known then as a thrifty ski-area owner, allowed selected workers to do. After nearly nine years patrolling, that season was to be his last. He had been saving money to attend Arizona State University and become a respiratory therapist. Friends recall him as the ultimate pro at whatever he did, from EMT to avalanche work. At a patrol banquet earlier he received “The Best Patrolman Ever” award. He had a girlfriend, played AA volleyball, drove a sports car, and was known as an “action man.”

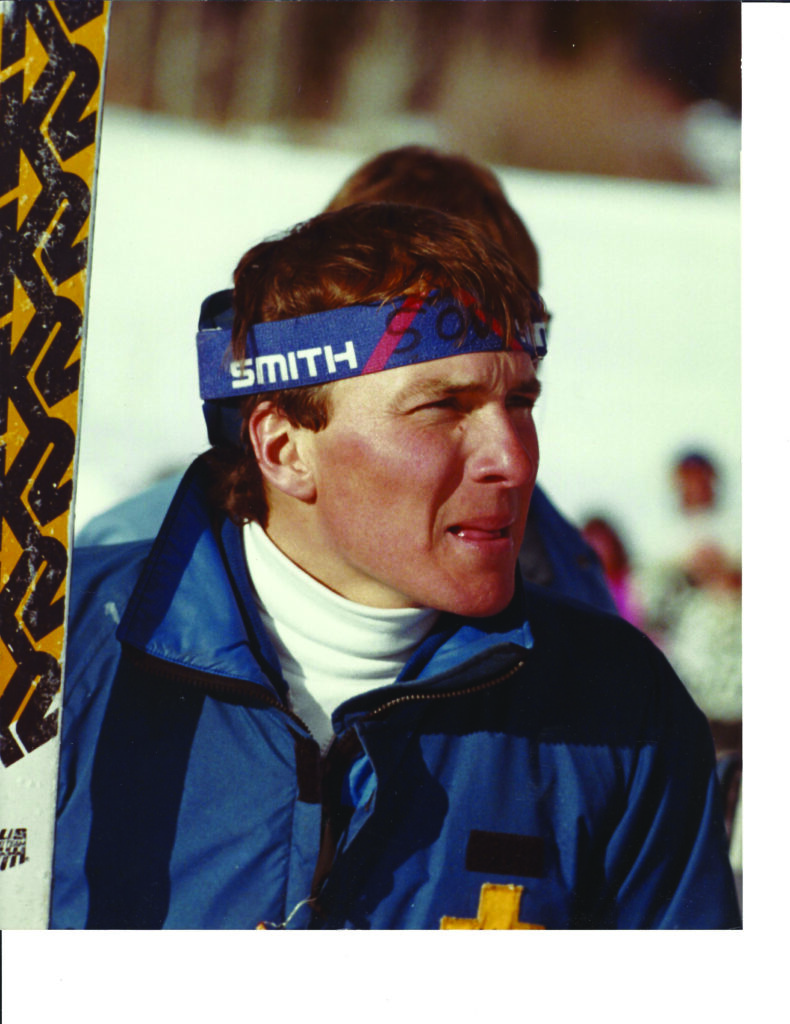

Craig Soddy, survived by his wife Amy, had some three years patrolling under his belt. Unofficially he acted as the patrol ski trainer, taking patrollers out to ski difficult snow on the narrow, unforgiving skis of the day. As a ranked tennis player and ski racer, he knew how to focus.

Fellow patrollers recollect him as serious on the job, “first class,” and an “all-around patroller.” Another characterized him as “Captain Enthusiasm.” He capped those qualities with his quick wit and sense of humor that put those around him at ease.

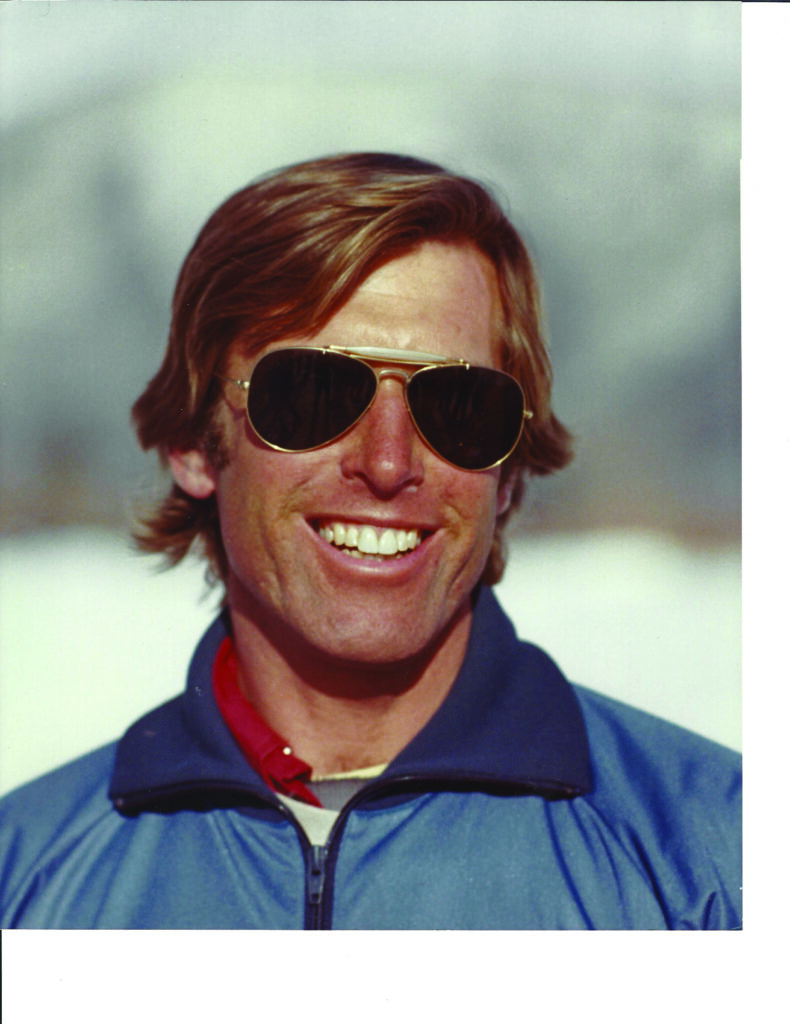

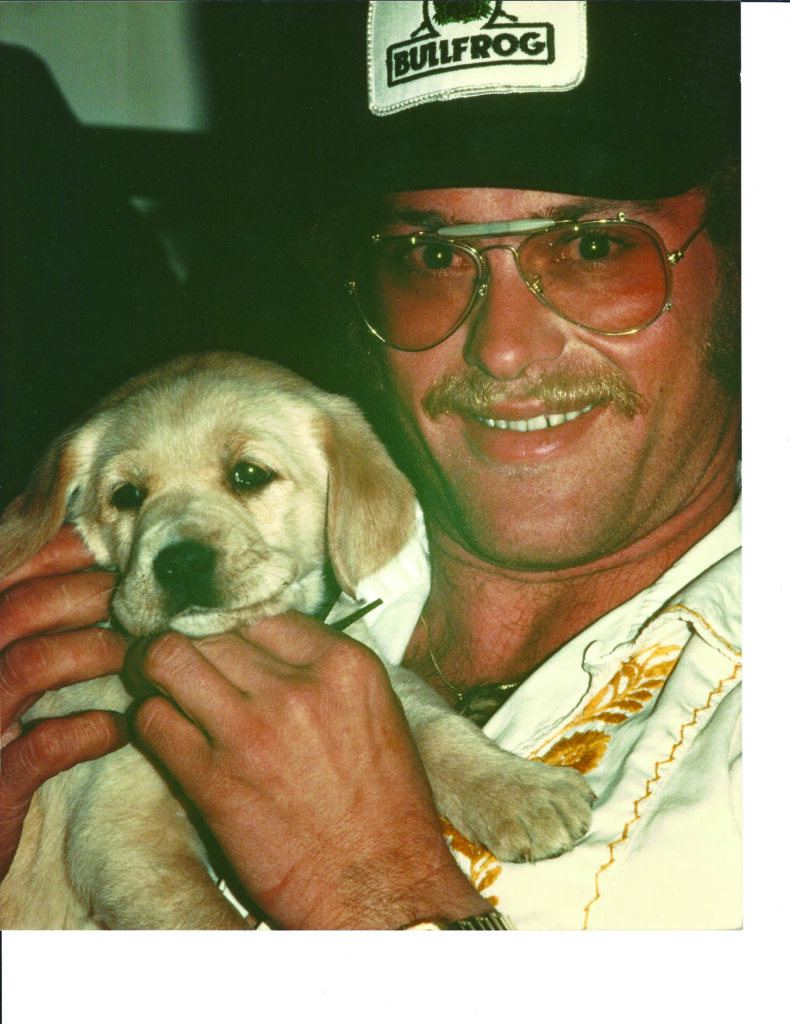

Chris “Crash” Kessler was the popular Aspen-raised kid on patrol. Ready to ski anywhere, any time, he kept his stuff in a pile called “the black hole” in the locker room. If anything was ever misplaced, patrollers quipped, “did you check the black hole?” He owned a horse, rode some rodeo, and taught country swing dancing at Aspen’s onetime Chisolm’s Saloon. Several years before, he had been buried and rescued from a slide onto Highlands’ P-Chutes Road. At the time of his death he was engaged to be married.

Notably, Kessler raised “Chopper,” Aspen’s first official avalanche rescue dog, who sired many pups in the valley. After Chris’ death, Chopper served at both Snowmass and Aspen Mountain. Chopper’s daughter, Bingo, followed him next on Aspen Mountain.

First descents

Perhaps Everest climber George Mallory’s saying, “because it’s there,” explains why so many have challenged the imposing ski terrain of the Bowl. But who skied it first?

Among the known early Bowl skiers, the adventurous Marolt family of Aspen have a picture of their great-uncle George Tekouzic standing in ski gear at the bottom of the Bowl, below Ozone, taken in 1941 before he went to World War II. The presumption is that he skied it.

The late Pete Luhn, one-time head of the Aspen Mountain packing crew, high-limb tree trimmer and letter-writing wag, claimed to be the first to ski the bowl from the top, in the early ’60s, “straight down from the peak, with a hangover,” he said. Some other high-mileage Aspen skiers say that Earl Shennum, who built the Ullr apartments on Main Street, could have blitzed the main Bowl first in 1963 or 1964.

On Feb. 15, 1968, Highlands ski patrollers Jim Flanagan and Matt Wells survived a large slide in today’s G-6 area, according to the periodical Colorado Geological Survey publication Snowy Torrents. Flanagan and Wells went to “check bowl conditions.” They threw “two 7-stick, 40 percent nitro” [dynamite sticks] from the top, one from the peak then one in their intended ski line, with no results.

First to ski, Flanagan became submerged in an 800-foot slide that cracked below Wells, who rescued Flanagan. Flanagan recounted that a form-fit snowball had packed his mouth so tightly that he was unable to breathe, yet he managed to chip it away with front-teeth bites until he could pull it out with his fingers. Both went on to serve long careers together on the Sun Valley ski patrol.

In the 1970s, way before regular control work of the terrain, numerous ski banditos poached the odds. Infamous brothers Theo and Ted Meiners, along with Dave “More Mud” Nelson, often took the handicap bet in the late ’70s. Theo went on to run Alaska Rendezvous Guides in Alaska, contributing much to modern snow science, before his death in 2012.

Post-1979, when Colorado passed the Skiers’ Safety Act, skiing in closed terrain within ski-permit areas put violators at risk of arrests and fines. This upped the bandito ante, precipitating a brief era when Highlands patrol chased stealth poachers. Ski-bum greats Rick Wilder and Denis Murray regularly ripped there in those days.

In 1982, Aspen mountaineer Lou Dawson joined what the underground called “The Highlands Bowling League.” This required a run down the gut from Highland Peak for membership. Some 100 feet in, bad luck and snow science intersected and a colossal avalanche took Dawson 1,200 feet to the flats, while his partner John “Izo” Isaacs watched. Spit out near the surface, Dawson endured two broken femurs and hypothermia before Izo found him and ski patrol evacuated him. Dawson’s written account of the event highlighted “a private moment” during the tumble, which lowered his risk-taking gambles from then on.

A 1970 independent group of skiers heading up the Bowl ridge to ski the Bowl. Photo AHS, Rick Lindner collection

A patrol-led Highland Bowl ski tour circa 1982. Snow Safety leader Kelly Klein stands with gloves in hand front row left. Assorted other Highlands ski school, patrol, and visitors stand behind Klein. Photo AHS, Andy Hanson collection

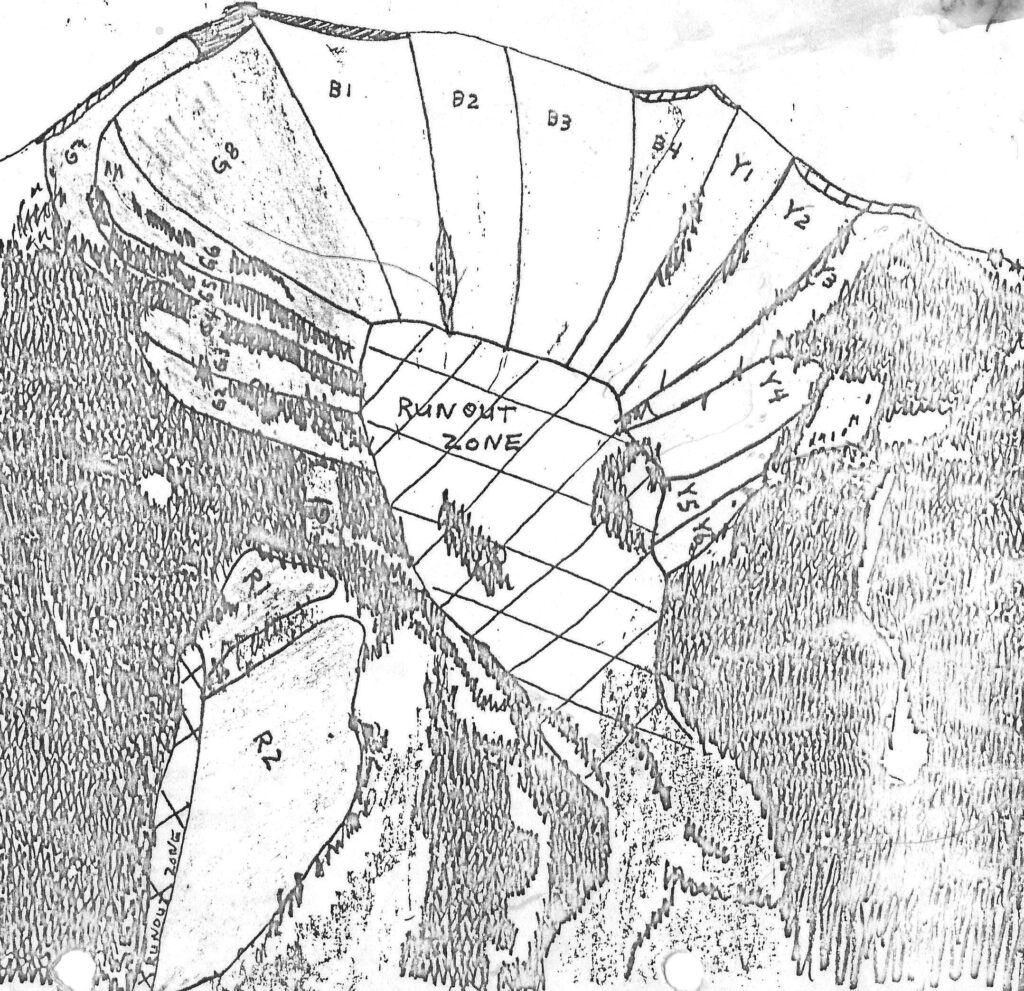

Former Aspen Mountain snow-safety director and 1970s Highlands patroller Doug Driskell recollects naming the G, B, and Y Bowl zones along with patroller Doug Childs after the colored waxes used for different temperature aspects: green for cold, blue for moderate, and yellow for warm. With time, the numbered zones acquired more delineations as patrol named specific snow-safety routes and ski lines.

Viable boundaries

Because Highlands owner Whip Jones wanted to keep his permit area boundaries viable, Highlands patrol examined the Bowl more closely in the late ’70s. Between 1980 and 1983 they started the Bowl snow-safety department, whose job was to figure out the Bowl so that they could conduct public ski tours.

The first Bowl keepers worked with a tight budget from Whip, as they explored, charted and tried to harness the skiing wilderness. The systematic techniques and tools they developed to manage the terrain grew from their studies of snow under the tutelage of iconic snow rangers such as Ed LaChapelle, Rod Newcomb, Liam Fitzgerald, Pete Lev, Betsy Armstrong, and Knox Williams.

At the risk of rhapsodizing a clich., ski patrolling in the ’70s and ’80s had a cowboy aspect to the job. Patrollers at major western ski areas routinely headed out the door in pairs on big snow days to their “avi routes,” their zipped coats stuffed full of two-pound charges secured within by a first-aid patrol belt. Tentacles of red fuses bristled out at the necks of their coats, extra ignitors lined their goggle bands over wool ski hats, and a lip bulge of chew sometimes accompanied their mission.

First Bowl keepers

In 1980, the first official Bowl specialists Tom Snyder, Kelly Klein and J.R. Rupinski, along with a number of patrol alternates, set to work evolving a disciplined approach, backed by a methodical set of record keeping, to what was then called “avalanche control.” In today’s more muddy-water jargon the job is called “avalanche mitigation,” lest litigation find monetary wiggle room.

In any case, observation, visitation, terrain history, snow study pits, temperatures, wind transport, storm data, explosives, early ski packing, ski cutting, and snow intuition were the major tools of boundary exploration then. Steeplechase served as a kind of Bowl training ground before Whip okayed moving up the ridge to the Highland Bowl as an expansion opportunity. Boot-packing in starting zones to bust up less-cohesive early-season faceted snow — known as depth-hoar — with the aim of nursing better bonding with subsequent snow storms remained a relatively new field tool then. The practice hadn’t yet become the well-financed wall-to-wall discipline deployed these days.

Multiple explosives in Highland Bowl and some in Olympic and Maroon bowls became part of the patrol’s widening awareness of the terrain around them in case of out-of-bounds rescues. The schooling then taught that explosives moved weaker snow out while stronger snow remained, a process called flush and refill.

With the Bowl’s beckoning presence, focus narrowed there between 1981 and 1984. Between 1981 and 1983, as understanding of Bowl dynamics increased, snow-safety guides led public tours up on skins before skiing the North Woods side. In the 1983-’84 season, Aspen Highlands ran helicopter tours. Most everyone on the patrol then wanted to go on a Bowl mission, so the early Bowl keepers, who characterized those days as “the greatest job you’ll ever love,” rotated patrollers through, studied the terrain, worked with the tools they had, and even invented some.

The Ultimate Weapon

Tours in those days rarely ventured deeper into the Bowl than north-facing G-6. The gut still stood as the respected gun barrel where caution ruled. The Bowl team set charges off in the Y-zones and along the ridge into the B-zones and then the G-zones before skiing the conservative north side.

They also set “trunk lines” with simultaneous detonator cord along the giant ridge cornice, at times rappelling into the Bowl to dig snow pits under the lee-side wind catch. Roped in, they deep-buried charges in the starting zones off the ridge, especially in wind slab, sometimes packing in ammonia-nitrate fertilizer for extra kick. Other times they set charges on bamboo tripods to employ air blasts over the pack. All this was part of the discovery process of how to make future Bowl skiing possible, but they couldn’t get the charges way down into the center of the Bowl into the deep pockets where they wanted them. For this they invented “The Ultimate Weapon,” a sling-shot device made of surgical tubing attached to an elk-skin pouch, which came from the hide of an elk shot by Patrol Director Mac Smith. Bowl leader Kelly Klein recounts, “You had to have a bit of the gunner in you to be the launcher.” Two others held the stretched tubing on either side. “You needed to have a low angle,” he said, like launching a mortar round, which is why the invention worked so well off the Highland ridge.

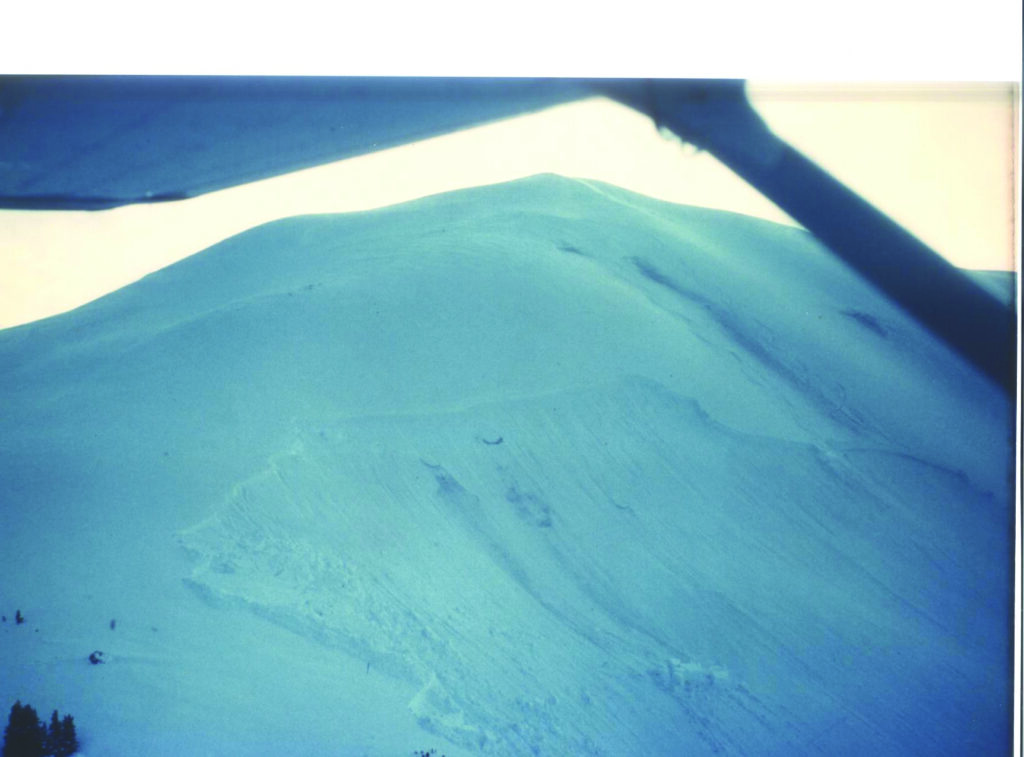

Bowl photo taken that same day from Snowmass patroller Tom Stiles’ plane shows the secondary, upper slide that overtook the three patrolmen standing on the bench in G-8, one-third of the way down. Photo Hal Hartman

Charge going off in upper B-1 area before the two shots in G-8, and before three skied down to the bench. Photo was recovered from Kessler’s buried camera.

In those days, fuses could be cut to a length deemed applicable to the job at hand. Ninety-second fuses worked in the elk-skin pouch, which because of its softness pocketed the charge well. With this new tool they propelled charges much deeper into the Bowl than they could before.

Helicopter access

In the 1983-‘84 season, the Bowl keepers upgraded their tools with the addition of helicopter tours. The ship picked people up in the Loge Meadow and whisked them to the top, and then from the Bowl flats up again for three laps. Between tours, snow safety used the ship to drop charges. Vietnam combat pilot “Blue” flew them on those ordinance runs, dubbed “the goat run.” The Forest Service didn’t want Bowl tours on days the resident big horns or mountain goats were up there. So the Bowl crew devised a pre-run strategy before each tour to check for critters. But of course the chopper spooked wildlife away, and then they did their control work. Blue nailed the chosen spots, tilting the ship in a tight hover so snow safety, strapped in, could ignite and drop charges from the door-less helicopter.

On March 8, 1984, the team dropped a four-pound charge and three six pounders from the chopper into upper G-8, setting off a large slide two-thirds of the way down. Between tours they had been scoping out the Bowl for a possible figure-eight contest for the annual Colorado Pro Ski Patrol convention, scheduled at Aspen Highlands on April 4. Getting that deep spot cleaned out reduced a hazard. If ever there was a year to showcase the Bowl as a canvas for a figure-eight contest, 1983-’84 was the one. Across Colorado the unusually stable equal-temperature (ET) snowpack inspired backcountry skiers and lulled avalanche forecasters into cautious comfort zones; some even ventured superlatives to describe the deep stability. Yet an early cold snap in January threw a wild card into the snowpack.

Surface hoar

Aspen Water Department records between 1934 and 2013 show a record 278 inches of snow for 1983-’84, with 2007-’08 coming in second at 250 inches, and 1994-’95 — a year in which Castle Creek Road closed due to slides — in third place with 239 inches. Typically, the Colorado climate produces intermittent autumn snows resulting in faceted, less-bonding crystals (depth-hoar) that form because of temperature transference from the warmer ground — which early-season powder skiers experience as “bottoming out.” Instead, in 1983-’84, the Colorado winter held off until a few days before Thanksgiving. November delivered a quick 55 inches of snow and December followed with 72 inches. Though some pockets of depth-hoar remained, the near nightly snows of December under cloudy skies kept nighttime temperatures from getting too cold. As the snow stacked past the “magic meter” depth, which helps insulate against temperature transference between the ground and snow surface or vice versa, faceted snow crystals became rounder and bonded throughout the snowpack. This yielded the unusual cohesion that Colorado skiers crowed about that year.

But along came one of Aspen’s pesky cold and dry Januarys that can produce surface-hoar, sun-twinkling feather-shaped crystals with lots of air space between, equivalent to winter dew. They form here and there without being a widespread layer, the beautiful bastards of a delicate dance between cold air, humidity, and low winds. Skiers sometimes hear the tinkling sound of surface hoar breaking around their boot tops on a cold first-track morning.

One anonymous ski bandito recalls seeing surface-hoar crystals high-up on Aspen Highlands on Jan. 1, 1984. The month ended with just 10 inches of snow. The 80 inches of snow that followed in February and March buried that layer and possibly other scattered plots of surface-hoar crystals.

According to records shared by the Aspen Highlands Ski patrol, a 10:30 a.m. snowpit dug on Jan. 10, 1984, at the top of South Castle Chute at Highlands, showed a new half-inch surface- hoar layer on top of a firm 60-inch snowpack of “advanced ET” (equal temperature) — by many measures a great snowpack. A 2:30 p.m. snowpit on Jan. 16 in upper G-8 showed traces of old surface-hoar at 33 and 51 inches down from the surface in a solid ET 64-inch pack; the bottom four inches were faceted crystals with bonding.

On March 29, a patrol team led by Snyder in upper G-8 threw charges and dug quick study pits before skiing down to the old March 8 slide path, where they set off a six-pound charge in a deep bore hole, with no signs of instability. Barring snowpack changes to come, this data reaffirmed stability and the possibility of holding the figure-eight contest there a week later.

March 31, 1984

The day started with a meeting where Snyder outlined a plan to his snow safety partners Klein and Rupinski. He wanted to retest lower pockets in the refilled section of G-8. Klein had been out for three weeks after knee surgery and was on dispatch handling the radio and phones. Rupinski was running the busy front-side operations — it was a Saturday — while Smith, the patrol director, had the day off.

Snyder had built confidence in upper-Bowl stability based upon his season-long observations that extensive explosive testing and snow pits confirmed. He enlisted Soddy and Kessler as partners that day, two experienced patrollers eager to draw Bowl duties. Of the three snow safety leaders, Snyder took a more offensive approach based upon his observed evidence.

Klein counter-balanced Snyder with his more defensive style, but he hadn’t seen nor felt Bowl snow for three weeks. Rupinski, too, took a conservative approach to snow safety operations. Snyder’s team would use the launcher off the ridge into the Y-zones, into B-1, and into upper G-8. As documented in Snowy Torrents, they would retest the March 8 slide area left of the March 29 tracks with explosives by sending one man in from the North Woods side to toss charges, followed by a hasty traverse back to the trees. Snyder agreed, but footnoted that he wanted to make a field assessment once on scene, depending on upper explosive results. At the time no cat track existed above Loge, nor were there kicked steps to follow; they broke their own trail. Between 11:30 a.m. and 1 p.m. the team launched five charges from the ridge into the Y-zones, setting off four- to six-inch soft slabs of new snow from the night before. By 2 p.m. they reached Highland Peak and paused while spotters Larry Lembke and Rupinski took a position across the Bowl near Hyde Park after throwing charges to secure the “Monback Traverse” back into Steeplechase from the Bowl, and to establish a safe rescue route. Then Snyder’s team launched a charge into upper B-1. No result.

Lembke and Rupinski watched as the 4-7 team’s next two charges in upper G-8 above the old March 8 slide path yielded no results. Soddy, Kessler, and then Snyder singly skied down upper G-8 between the explosion craters. Snyder checked the snow profiles in the holes. The three then met at the North Woods edge, consulted, and traversed singularly to the G-8 bench one-third of the way down, Lembke said. Rupinski and Lembke called them and advised caution as the team proceeded with an alternate plan, which put them below the pack that hadn’t slid all year. Snyder replied, “Nothing is going to slide today. It’s bullet proof.”

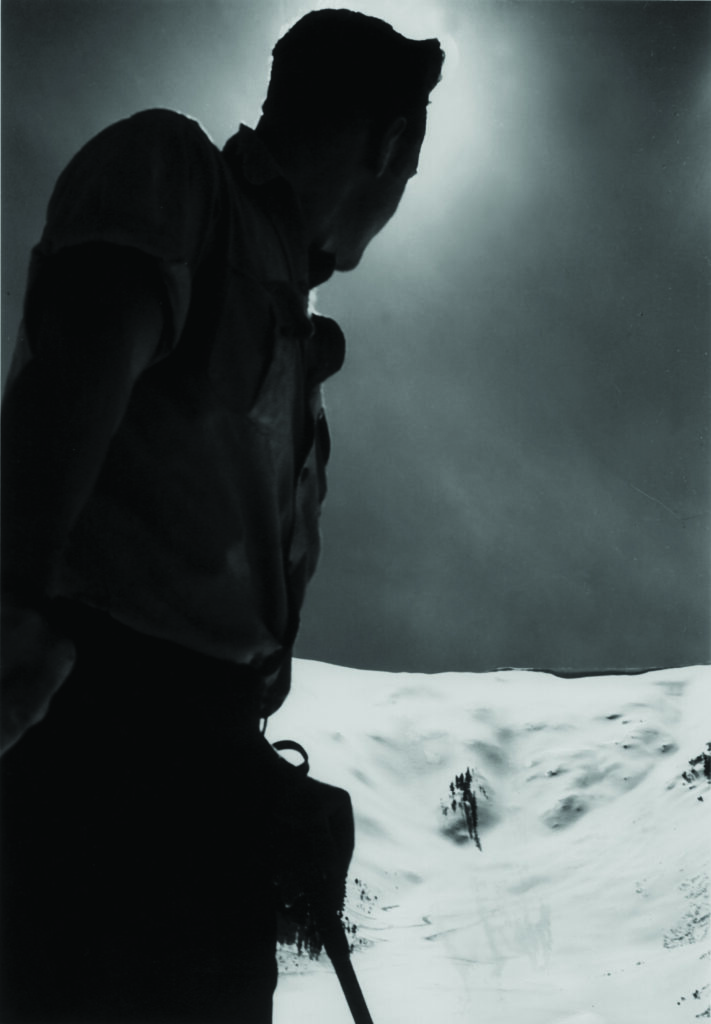

One of the three patrolman caught that day in the slide, skiing down the Bowl from the top through the upper part that overtook the three while standing on the bench in G-8. Photo was recovered from Kessler’s buried camera.

One of the three skiing into the top of the Bowl, day of slide. Photo was recovered from Kessler’s buried camera.

The second shot

As is the case in snow safety, plan changes based upon observed field conditions may be appropriate or inappropriate. In this case, Snyder made a field decision based upon his confidence that he could safely assemble there on the bench with the launcher rather than stage from the north-facing trees. The Hyde Park spotters were not happy that Snyder changed from the plan of throw and retreat. But Snyder’s view was that they couldn’t reach the desired spots without the launcher and the snow above them had proven stable.

From their position on the bench 30 feet above the March 8 slide-path crown, they launched the first charge into the old slide path to their lower left with no results. The second charge, placed below the bench and above where they safely skied on March 29, was a different story. A soft-slab slide broke off the old crown face below Snyder’s team. For a moment the mission was a success in that it cleared out Snyder’s pocket in question.

Rupinski, who now lives up the Frying Pan in Basalt, reflects with long-carried feeling that “for a few seconds the guys probably thought they were OK. Then it looked like a huge pane of glass breaking in slow motion.”

And Lembke, who was an army-trained ski patrolman in Germany before Highlands and who now lives in Grand Junction, said, “The three guys looked like dots standing there. Then a fracture came up from their left below them, crossing above them. They disappeared in a big churning snow cloud full of chunks and we couldn’t track them.”

What happened

After the initial tragedy and rescue, Whip Jones closed the Bowl and no patrollers were allowed back in to study the fracture lines or crown faces. But evidence from previous snow-study files and pictures of the slide path taken that day from a plane paint a picture of likelihood. The initial lower slide below the old fracture line slid to the ground on a faceted base layer, noted in Snyder’s snow-pit profile dated March 29, 1984, which was why he was retesting those pockets with explosives. Because the March 8 slide path essentially began a new winter as it refilled, base facets remained, while the mid-pack developed a rounding, bonded snow. This created a strong arch-like effect that often keeps Colorado snow in place until, provoked or unprovoked, a slope might slide.

Consensus agrees that the upper, secondary slide that overtook the team slid on a buried surface-hoar layer hidden there in early January. Aerial pictures show that the resulting hard-slab avalanche with boulder-sized chunks slid on a shear plane in the lower mid-pack, about where the January surface-hoar would have been hidden. Remember, though, that buried surface-hoar patches are elusive, and are not everywhere one digs a pit.

The theory goes that the three earlier charges they had thrown above before entering collapsed the surface-hoar into shear planes deep in the pack, like flattened card houses. Since the snow in the Bowl may be considered as one piece of complicated fabric, the year-long stable pack above Snyder’s team probably slid like a blanket off a bed, as the lower slide collapsed and pulled.

The combined avalanche in total measured 1,000 feet across. The crown broke 300 feet above the team at an 11,800-foot elevation on a northeast-facing slope exceeding 35 degrees, according to The Snowy Torrents. That upper elevation avalanche overran the bench the patrollers stood on.

A note card in the Bowl data file from earlier that year in Tom Snyder’s handwriting reads: “The energy of a fracture line can have a thousand times the energy of a skier’s weight on the snowpack and can propagate into areas which may appear stable.”

The rescue

At 2:40 p.m. Lembke called patrol headquarters, then located where Cloud Nine Restaurant is today, saying there was a “major slide in the Bowl and three patrolmen were caught.” Lembke and Rupinski traversed in on an angle and began a difficult zig-zag pattern down the vast debris field, searching with their avalanche beacons. Within minutes, while carrying a metal grain scoop shovel, Lembke picked up the first signal and began digging. Patrollers Jeff Melahn and Pat Fort came into the Bowl from the Loge patrol room and along with Rupinski located the other two signals, as more backup patrollers arrived. Big slab chunks in the debris gave false probing strikes, yet all three signals were pinpointed within five minutes and patrollers began digging.

In those days digging went straight down to the signals. This required a wide hole to manage a deeper burial. Today, preferred technique angles in from below the signal, throwing the snow downhill. Yet busting up avalanche-compacted snow with a mere shovel still requires a mind-numbing adrenalized effort.

Records show that patrol recovered Snyder first at 3:15 p.m., five feet down; Kessler at 3:25 p.m., six feet down; and Soddy at 4 p.m., eight feet down. After clearing the victims’ airways of snow, patrollers on scene did two-man CPR.

The tour helicopter was not available. Greg Mace of Mountain Rescue alerted the “First Tracks” helicopter out of Marble, which quickly arrived at the bottom of the Bowl. In three trips, a different patroller doing one-man CPR in the helicopter accompanied each victim to Aspen Valley Hospital, where all three were pronounced dead of massive traumatic injuries. All patrollers were out of the Bowl by 5 p.m. and at patrol headquarters for debriefing. That evening they gathered at patrol supervisor Dick Merritt’s house for food and drinks, and to begin the long process of reflection.

Second chapter

Chapter one concluded, and like hallowed ground, the Bowl remained closed until 1988, “when we first started tiptoeing in there again” said Jeff “O.J.” Melahn, today’s head of Aspen Highlands Snow Safety. “We learned that even stable starting zones can be triggered remotely.”

With today’s early season bootpacking crew, along with systematic application of explosives and continuing skier compaction, “We disrupt every layer and shear plane wall to wall from the ground up, beginning with the first snowfall. Our goal now is to try and preserve every flake that falls, versus flush and refill,” Melahn said.

Chapter two began in 1993 when the Aspen Skiing Co. bought Highlands. The Bowl held marketing value not only because of its splendor but because of the emerging popularity of radical skiing terrain.

Patrol Director Mac Smith had already led the effort to open Steeplechase and Olympic bowls, and he eyed Highland Bowl next. Patrollers Melahn, Kevin Heinicken, and Peter Carvelli became the new Bowl keepers, who took Bowl science to the next level. They opened the Bowl gradually between 1997 and 2000, with a full public opening in 2002-2003.

Upon reflection, J. R. Rupinski concludes, “Opening the Bowl happened in stages as it should have. Just stand at the bottom and watch all the smiling faces coming out of there.” Though some say that the innate sacredness of the Bowl deserves less traffic, those privileged to enjoy the Bowl experience now might reflect on how to “pay forward” their exhilaration to help others, in honor of Tom Snyder, Craig Soddy, and Chris Kessler.

Aspen Journalism is an independent nonprofit news organization. Visit their website for more.