Story & photographs by Jonathan Preuss, originally published in TAR 41.1

It was my third day out in the Mushroom Ridge area. I was feeling confident that I knew what was going on in the snowpack. A couple of waves had brought new snow to the mountains after a three-month-long dry spell. This time of year people break out bikes and load up summer wax on skis, meanwhile it was dumping cold snow in the mountains! I love getting out this time of year and skiing steep lines. The new dry snow can change to mashed potatoes within minutes so it’s necessary to have a flexible schedule to get the goods.

I put out a desperate message attached with some powder photos from the day before into an Instagram post. “Hit me up if you want to ski tomorrow!” An old friend who I haven’t skied with in a long time reached out. I told him to bring all the sharp things he owned and meet at my place. Lee showed up and I opened my laptop with a proposed ski tour plotted on CalTopo. One couloir would give us access to the area referred to as Gnarnia and then we’d climb back out, then traverse a ridge to a north-facing couloir. He looked at me and said, “This is exactly what I wanted to do today.” I pointed out three possible exits from our last run, which would bring us out of the Grand Prize drainage.

There are no daily avalanche forecasts delivered this time of year, so it becomes even more important to stay on top of the weather and see what is going on in the snowpack. I mentioned to Lee that the best snow right now was on the north faces (as per usual) and the only stability concern I had was Wind Slabs and Dry Loose problems. My thought was to stick to confined terrain features (couloirs), where a precise slope cut could clear away any issues. I wanted to steer clear of big, open faces where it’s harder to safely manage wind slab problems.

At the trailhead we talked about rescue equipment, first aid kits, bivy tarps, and repair kits. Then we separated gear between us to travel light and fast. I mentioned where my InReach device was kept and how to use it. This is something I do with anyone I don’t tour with on a regular basis, especially my guests I’m taking out for the day. We did a transceiver check and marched up the skintrack.

LEe looked at me and said, “This is exactly what I wanted to do today.”

Lee commented on the drifting snow once we got higher on the ridge. The winds had basically moved snow from most aspects within the last week, so it was challenging to know exactly where the most recent load was coming from. It was going to require looking at each slope individually to assess where or if it was loaded with any new wind transport. There were no recent slab avalanches observed.

We made it to the top of Mushroom Ridge, where we had to navigate through small rock bands and snowfields. I poked my pole through the snow to feel if there were any slabs sitting over weak layers. Nothing stood out in my rudimentary stability tests. I elected to downhill skin across the small start zone (~50’ long) to avoid multiple transitions. Looking back on it now, it would have been much safer to stick to the ridge and not add too much time.

We stood at the top of the first run, a 35°+ NNW couloir that had multiple sections to regroup on the way down. I set a slope cut down to a nice moat that was created over the season with the prevailing NW winds, then continued down fast snow that had pockets of wind-blown pillows for some softer turns. Nothing moved and I yelled up to Lee to come down to me. He skied down and then continued down the last pitch into the aprons. Just as he started to descend, a local couple skied down from the Upper Gnarnia basin. I shouted to him that there was another skier, but he couldn’t hear me.

I don’t like dropping in above other parties. It’s bad practice in my mind. If we were to trigger an avalanche, it would be on top of them and possibly add more people buried. But everything was fine and we skinned up to examine our next climb.

The upper basin was wind blown off the ridges and looked like terrible bootpacking conditions. We decided it would be best to continue down and then wrap around the ridge to gain point 10,126’. There was another small couloir feature to connect us downhill. It was a short, north-facing feature that I entered with caution. I skied to the rib in the middle and posted up to have eyes on Lee as he skied through the whole pitch. When I can’t see the whole descent, I will try to get down to a safe location so I can see the entire line. In the event it slides, you can see the rider and get a last point-seen location. It was another solid run with even more ski pen (aka deep snow) thus more powder shots!

The next climb was up a steep west face that connected to a ridgeline. We skinned up it and got a view of our previous two runs. Another party of two was skinning out a wide couloir feature back to the Horse Creek exit (refer to “Other Party of 2” GPS track). The slope was 35–45° (based on Slope Shading) and N/NW facing 9200–9500’. I must have subconsciously acknowledged they were moving through steep terrain with no consequences. This undoubtedly created a bias for the day about stability being good.

We finally got up to the last couloir of the day and this is the one I had been drooling over on Google Earth for a week now. I knew it was going to ski great because I skied a similar feature four days earlier and there was more snow out there now. When we got to the ridge to look into the slope, it was riddled with cornices and the entrance looked too rocky to descend from the top. I looked for another way to access the run. I ran up and down to get different views, looking for a weakness in the corniced ridgeline. There was a small entrance that had a little cornice that we could cut loose using a ski to saw off the cornice, leading to a small, delicate traverse that would require walking over lots of rocks to get the couloir. I proposed the plan to Lee; he was game for it. So we went to work, carefully turning our way into the run and across the face.

After some debate on whether we were skiing or rock climbing, we were in! We skied it in two pitches, regrouping halfway down. It was all-time skiing and we wished it lasted for another 1000’. At the bottom, we looked back up and talked about the run. We discussed our exit plan; I again brought up all three exit strategies in no particular order.

OPTION 1 was to exit through a small, steep section that looked windloaded and would require gaining the same ridge we had just walked up. Lots of booting over loose rock—we quickly said no to that option.

OPTION 2 was to gain the saddle next to where we ended the run. It was a small face with a 200’ band of red (35–45° slope shading). This was the fastest way out and was calling our names.

OPTION 3 was to continue down the basin and wrap around through lower angle terrain. It was the longest way back to the Western Home exit, but by far the safest. The steepest section of this route would be on an east aspect, which was less likely to have any avalanche problems on it with recent sun exposure.

We talked over all of the options and our tired bodies kept going back to Option 2. We had a great day and we were now “smelling the barn.” When analyzing skin tracks in avalanche terrain, there are a few points I take into consideration if there are no safer options to move through that terrain and have to ascend steep slopes:

- Is there a Persistent Slab problem? If the answer is NO, then proceed with caution. Dig to visually verify and periodically check to confirm throughout the climb out. Other avalanche problems should be considered too.

- Stay on the lowest slope angle as possible. Statistically speaking, the closer you get to the magic number of 38°, the more likely the slope is able to trigger an avalanche. If there is a collapse in a layer, it will travel faster and possibly longer in steeper terrain, thus creating a larger avalanche with more snow to knock you over or get buried deeper.

- Stick to the deepest snowpack or no snow at all. I’m sure this point will open up some discussion. Some would argue if you are thinking in this manner, then maybe you shouldn’t be on that slope. Thinner snowpacks are notorious for being trigger points in avalanches. We are traveling and impacting the snow closer to suspect layers and therefore more likely to initiate failure. So if you stick to the deeper snowpack, you are less likely to trigger anything sitting below in the snowpack, but if you do trigger an avalanche, it will likely be a hard slab which is more destructive and challenging to get off. It is always safer walking up on rock, where you aren’t connected to the snowpack, but it is slower and less efficient to carry your skis/boards on your back. Keep in mind that traveling over little sections of snow that are connected to bigger slopes can be ideal spots to trigger avalanches as well.

- Avoid being above terrain traps (gullies, cliffs, creeks). Make sure your route has a clean runout and an apron, rather than channelized terrain to minimize consequences and stay on top.

- Are there any environmental factors increasing the chances of causing injury? Is the sun influencing slab consolidation or introducing water into the snowpack to cause Wet Loose or Slab avalanches? Is there rock or cornice fall from above and could we be in the line of fire?

I started to break trail up the exit Option 2 (marked in yellow) towards the saddle that would give us a fast exit back to our vehicle. We were halfway up it and I looked back at Lee and asked if we should ski another run down the skintrack. We agreed it would be great snow, but would make the decision at the top.

I was about a switchback away from being in the clear at the top when I saw snow moving all around me. I remember thinking, “Fuck, not again.” I somehow turned myself around and tried to run over (we were in tour mode) towards the flank of the slab. After I fell over on my side, I knew I was in it and reached for the trigger on my avalanche airbag. I could hear it inflate the large red balloon around my back as I tried to push to keep myself on top of the debris. I came to rest on the bed surface and looked up to see what was above me and see if I could see Lee. Then I looked down to see the slide continue down the mountain and I could see Lee on top near the bottom. Everything halted and I shouted down, “Are you alright? Do you need help getting out?” I could see he was on top and only partially buried, so I ripped off my skins and skied down to him.

We were in awe of what just happened. I remember being angry that I just got caught in another slide within three years almost to the day. I felt “like a boxer that’s been knocked down and lost his step”—Senses Fail. How did I let that happen again?! Then I couldn’t understand why I felt so calm. The first slide I was in I thought, “I could die in this right now.” But why didn’t I feel the same rush of adrenaline with this one? Was it because I didn’t hear the collapse or that I could feel the bed surface and knew it wasn’t too deep? I knew the runout was clean and a good place to get caught. It was a strange feeling.

Lee was only buried knee deep and right side up, so he was able to wiggle his way free. We talked about the slide and walked through the chain of events. Lee remembered us both shouting avalanche, when I only remember looking at him right before my trauma response went into fight (beast) mode. He heard the collapse when I didn’t hear anything. I remember getting a bad feeling maybe 30 seconds or so before triggering the avalanche. I have thought back on that feeling a lot since that day. What could I have done at that moment? Calmly tell Lee we should carefully transition to downhill-mode as gently as possible? Should we have just pointed it downhill with skins on and hope we don’t wreck from downhill skinning? What if we triggered it on the way dwn? Then we would have all of that snow moving above us and be more likely to be buried and not have a chance to get off the slab. Unfortunately, I don’t have an answer to this question, but I can’t help but think about intuition and gut feelings. They are something you shouldn’t just push away.

We came up with a new game plan to get out of there. It didn’t look like too much hangfire above the crown and maybe we could boot up through some rocks. If the hangfire were to release, it wouldn’t be that big and we would be able to get off of it easier than what we just experienced. Option 1 looked wind loaded with snow and we would have to repeat the same ridge bootpack which was slow and tiring. A week later, there would be a visible crown near this option. Option 3 still felt long and we just wanted to get the hell out of the mountains.

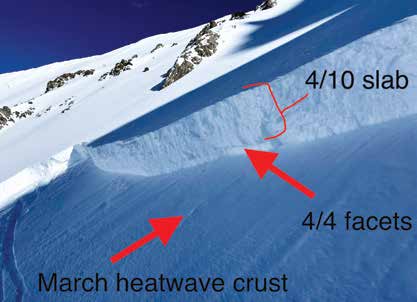

So we skinned up the same slope again. Having to climb it again felt like rubbing salt in the wound. I could feel the facets sitting on top of the bed surface which felt like walking over a slick layer of sand. I would occasionally take video and photos to document what happened. When we got up to the crown, I ran my fingers through the profile. I visually noted the hand hardness of all the layers and where the failure occurred. There was about a 55cm F->4F soft slab sitting over 5cm of faceted snow 1–2mm, which stood on top of a stout Melt/Freeze crust which formed in a week-long heat wave in March. It was an obvious weak layer that I missed. I must have skied over this layer on other slopes within the last week. But now it had a consolidated slab on top of it.

After looking at some nearby weather stations, I put together the pieces that I missed by not digging into the new snow. On April 4, a small storm dropped 4-6” (SWE 0.40–86”) followed by two cold nights which caused it to facet. On April 10, that layer was buried by numerous days of moderate increments of snowfall (23–29”, SWE 1.10–2.25”) over a seven-day period, creating a heavy-over-weak setup in a time when most of us thought we were just skiing powder in a springtime snowpack (melt freeze cycle). The snow scientist in me wanted to do some stability tests in a crown profile to see how reactive that layer was and link some corresponding numbers to it. I looked up at what looked like small hangfire from down below and my nerves twitched with the thought of tapping on that slab. We didn’t like our initial plan to bootpack through a small rock couloir, which now looked like 40 feet of tromping over a slab which had avalanched less than 30 minutes ago. A rock rib gave us some more elevation to get closer to the ridge. We executed the plan and made it to the saddle, then transitioned to skiing and moved quickly through runouts back to our vehicle. The hot spring snow turned back to solid snow (aka breakable crusts) and made for survival skiing.

So what did I learn? If I want to grow old in the mountains, I will need to increase my margins of safety. This would be easy to do by just avoiding avalanche terrain, but I know this is unrealistic because I enjoy steep skiing, and as a ski guide, guests request that type of terrain. How can I manage skiing in steep terrain, but not get caught in another slab avalanche? Both times I have now been caught in avalanches when I was skinning. Sometimes there is no other way to get up to the top or through mountains without doing this form of travel. But now I will have to add some more rules to this is an acceptable risk in addition to the previously mentioned points.

Here are some thoughts I have come up with:

BURNOUT It was the end of a long season filled with managing a small company through COVID and a low snow year. Between guests and guides getting sick and figuring out how to find the good snow after weeks to months of no snow, I was ready to turn the brain off and just go ski some lines. I wasn’t tracking the weather as closely as I should have and wasn’t taking the time to dig, to see what I was missing out there. Burnout comes most years with seasonal guiding work and will have to be taken into account when skiing in the spring. There is no “taking days off” in the mountains. You have to be fully present and actively reading the current conditions. The day you let your guard down in high risk areas could be the day the mountains show you their true power.

WINTER RETURNED I was skiing around like it was a locked-up spring snowpack capped with new snow, thinking it was glued to that hard crust from the March heatwave. I wasn’t adjusting my mindset (refer to Atkins paper on Ying, Yang, and You) to the fact that it was snowing large amounts with periods of time for weather to change those layers. We had a winter with months of no major change in the snowpack. The 12/11 layer plagued us during the beginning of winter as it was trending towards a Deep Slab in certain locations, but ended up going dormant. After that, we have months of Open Season with no major changes in the snowpack. But then winter turned back on in April and May, so I should have accounted for that change with an Assessment mindset. Whenever it snows, we should be digging in the snowpack to see how new snow interacts with old snow.

OTHER THOUGHTS The last point is more of an observation than a lesson. When Lee and I debriefed our incident, he mentioned that he knew he was going to be alright because I was wearing an airbag and was likely to stay on the surface and thus could dig him out. This is a new (to me) concept that I haven’t thought about before.

Within the coming weeks, the 4/10 persistent weak layer would catch other backcountry travelers off guard. A group of snowmobilers would remote trigger another large avalanche six miles north near Phyllis Lake.

There was chatter about another group triggering an unreported avalanche in the Sawtooth Range. A week later, a guided group triggered Cody’s Bowl while skiing down. Luckily, the guide was able to ski off the slab and the group was posted up in a safe position on the ridge. The guide trusted their gut instinct which told them to make that last turn right towards lower angle terrain. That gut feeling may have been the key to not getting swept down that path.

Sometimes the mountains feel like a drug that is impossible to give up. They allow us to run away from problems that we face in our real life. But even the safest drugs have shady aspects that require attention, trepidation, and reverence. We have to respect the mountains and in return they will let us come home at the end of the day. ⬢

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jonathan Preuss “JP” has been guiding in the mountains of Idaho since 2010. He studied Outdoor Education at Johnson State College. He has been an operations manager, SAR member, educator, and an AMGA certified ski and rock guide. He likes spending time hunting avalanches and continuing the journey of snow science, which he will do this winter as the newest member of the Sawtooth Avalanche Center (SAC) forecasting team.

Note from the author: Special thanks to Dan Schwartz for his editing skills and to Lee for helping me share this experience with you all.

HEADER PHOTOS, L-R: (1) A triggered avalanche with two skiers caught and one partial burial. Grand Prize, 9650’, NNW, ~35 (start zone), SS-ASu-R2-D2-O, 55cm thick, 290’ wide, 460’ vertical, 930’ length of path. (2) Lee skiing down the first couloir into the land of Gnarnia. (3) Lee looks up at the corniced ridgeline that halted access into our last couloir of the day. (4) Lee carefully walking over rocks to get to the line.